Difference between revisions of "Trout Reduction Efforts"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

</table> | </table> | ||

| + | [[File:NatalOrigins.jpg|center|600px]] | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

------------Portal list on righthand side----------> | ------------Portal list on righthand side----------> | ||

|style="width:60%; font-size:120%;"| | |style="width:60%; font-size:120%;"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Findings from the [[Natal Origins Project (NO)]] Project== | ||

| + | *There is a low probability for an individual rainbow trout to move large distances. | ||

| + | *Abundance is a key factor: the more rainbow trout upstream in the Lees Ferry reach = more trout will move downstream to the LCR reach in search of unoccupied habitat | ||

| + | *Condition may be a secondary factor: when food resources become limited, rainbow trout will move downstream in search of food | ||

| + | *Recruitment in the reach below the LCR can be accounted for solely by immigrants from upstream sources | ||

| + | *Food limitation led to the collapse in the trout population, and by extension also likely happened in the downstream reaches. | ||

| + | *Inflow hydrology and reservoir limnology likely govern the quality and quantity of nutrients supplied to the downstream river segments. | ||

| + | *[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Nutrients Nutrient limitation] is hypothesized as being the “BIG HAMMER” to the riverine ecosystem, which needs to be evaluated in greater detail in future research. [https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/17jan26/AR16_Yard.pdf] | ||

| Line 36: | Line 46: | ||

|class="MainPageBG" style="width:55%; border:1px solid #cef2e0; background:#f5faff; vertical-align:top; color:#000;"| | |class="MainPageBG" style="width:55%; border:1px solid #cef2e0; background:#f5faff; vertical-align:top; color:#000;"| | ||

{|width="100%" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" style="vertical-align:top; background:#f5faff;" | {|width="100%" cellpadding="2" cellspacing="5" style="vertical-align:top; background:#f5faff;" | ||

| − | ! <h2 style="margin:0; background:#cedff2; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #a3bfb1; text-align:left; color:#000; padding:0.2em 0.4em;"> | + | ! <h2 style="margin:0; background:#cedff2; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #a3bfb1; text-align:left; color:#000; padding:0.2em 0.4em;"> Trout Removal Efforts </h2> |

|} | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Removals at the Little Colorado River== | ||

| + | |||

| + | During 2003–2006, over 23,000 nonnative fish, including rainbow trout (19,020; 82 percent) and | ||

| + | brown trout (479; 2 percent), were removed from a 9.4-mile reach of the Colorado River near the LCR | ||

| + | confluence (Coggins and others, 2011). Concurrent with mechanical removal, mark-recapture studies | ||

| + | within a control reach of river 20 miles upstream of the removal reach demonstrated a system-wide | ||

| + | decline in both rainbow trout and brown trout that was unrelated to the fish removal effort. During this | ||

| + | same period, a rapid shift in fish community composition was observed in the LCR reach (the mainstem | ||

| + | Colorado River upstream and downstream of the LCR; see reach 2 in fig. 1), from one dominated by | ||

| + | cold-water salmonids (>90 percent), to one dominated by native fishes and the nonnative fathead | ||

| + | minnow (Pimephales promelas) (>90 percent). Thus, our understanding of the efficacy of mechanical | ||

| + | removal was confounded by an external systemic decline, particularly in 2005–2006 (Coggins and | ||

| + | others, 2011). Another removal effort took place in 2009, with around 2,500 nonnative fishes removed | ||

| + | from the LCR reach (Makinster and Avery, 2010). Subsequent electrofishing in the LCR reach showed | ||

| + | that the number of rainbow trout and brown trout was higher after 2008 (fig. 4; Makinster and others, | ||

| + | 2010), but the catch rate declined for rainbow trout and brown trout after 2014. The average catch per | ||

| + | trip (based only on the first two passes of electrofishing to standardize across years) for rainbow trout | ||

| + | was 209, 294, 460, 67, 18, and 56 between 2012 and 2017, and 2, 10, 5, 2, 0.3, and 2 for brown trout | ||

| + | over the same period (C.J. Yackulic, GCMRC, written commun., April 3, 2018). [https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181069] | ||

[[File:TroutFlows.jpg|center|500px]] | [[File:TroutFlows.jpg|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[[File:TroutRemoval.jpg|center|500px]] | [[File:TroutRemoval.jpg|center|500px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Bright Angel Creek Removals== | ||

| + | |||

| + | A second effort to control nonnative fish, specifically brown trout, was implemented in 2002 in | ||

| + | Bright Angel Creek. As recently as the 1970s, rainbow trout dominated the fish community in Bright | ||

| + | Angel Creek and brown trout were rare (Minckley, 1978), despite this tributary having been stocked | ||

| + | with brown trout, twice in 1930 and once in 1934. After the 1990s, however, brown trout became a | ||

| + | predominant component of the fish community in the creek, and a corresponding decline in native fish | ||

| + | such as speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) was observed (Otis, 1994). Bright Angel Creek is now a | ||

| + | principal spawning site for brown trout, and an aggregation is found in the Colorado River near the | ||

| + | confluence with Bright Angel Creek (fig. 3; Valdez and Ryel, 1995; Makinster and others, 2010). | ||

| + | In an attempt to restore the native fish community of Bright Angel Creek and to reduce the threat | ||

| + | of predation to humpback chub in the Colorado River, a program of mechanical removal of nonnative | ||

| + | trout from Bright Angel Creek was implemented. From November 2002 to January 2003, a weir was | ||

| + | operated near the creek mouth, which resulted in the capture of over 400 brown trout as part of an initial | ||

| + | feasibility study (Leibfried and others, 2005; fig. 5). In 2006, the Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction | ||

| + | Project Environmental Assessment (EA) and Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI; National Park | ||

| + | Service, 2006) identified goals and a strategy for reducing numbers of brown trout. This project was | ||

| + | initiated in cooperation with the USFWS in 2006–2007 (National Park Service, 2006; Sponholtz and | ||

| + | others, 2010) following the feasibility study. This effort was resumed in 2010 (Omana-Smith and others, | ||

| + | 2012) following the 2008 and 2011 Biological Opinions on Operation of Glen Canyon Dam (U.S. Fish | ||

| + | and Wildlife Service, 2008 and 2011) that identified conservation measures to conduct trout reduction in | ||

| + | Bright Angel Creek and to establish multiple self-sustaining populations of humpback chub in Grand | ||

| + | Canyon tributaries (Valdez and others, 2000). [https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181069] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Current operations under the Bright Angel Creek trout control project were established through | ||

| + | the NPS Comprehensive Fisheries Management Plan (CFMP; National Park Service, 2013a). From | ||

| + | 2010–2012 trout reduction efforts included installation and operation of a weir and backpack | ||

| + | electrofishing in the lower 2900 meters (m) of the creek (confluence to Phantom Creek; Omana-Smith | ||

| + | and others, 2012). Beginning in fall of 2012, removal efforts were expanded to encompass the entire | ||

| + | length of Bright Angel Creek (~16 kilometers [km]) and Roaring Springs (~1.5 km). | ||

| + | The operation of the weir was extended from October through February to capture greater | ||

| + | temporal variability in the trout spawn (Omana-Smith and others, 2012; National Park Service, 2013b). | ||

| + | Electrofishing removal efforts, led by NPS and GCMRC, also occurred in the mainstem Colorado River | ||

| + | in the Bright Angel Creek inflow in 2013 to 2016 (C. Nelson, USGS, oral commun., January 27, 2016). | ||

| + | The brown trout removal effort in Bright Angel Creek proper has continued annually from 2010 to 2017 | ||

| + | (Schelly and others, 2017). Across the most recent five seasons of removal, encompassing the entire | ||

| + | Bright Angel Creek drainage, brown trout captures have declined steadily and considerably from 12,467 | ||

| + | fish per year in 2012–13 to 4,902 in 2016–17, despite a similar level of effort each year. This decline | ||

| + | has been most pronounced in age-2 and larger fish, with cohorts of age-1 fish produced in the previous | ||

| + | season remaining fairly stable from year to year (fig. 6). A large cohort of age-0 fish was apparent in the | ||

| + | winter of 2013–2014, perhaps a result of compensatory survival following removal of larger brown | ||

| + | trout. Similar relative declines were seen in rainbow trout, which were also removed, while native fish | ||

| + | abundance and upstream extent increased, particularly in speckled dace (B. Healy, NPS, written | ||

| + | commun., March 5, 2018). [https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20181069] | ||

<!-- | <!-- | ||

| Line 54: | Line 131: | ||

*[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=FISHERY Rainbow Trout Page] | *[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=FISHERY Rainbow Trout Page] | ||

*[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Brown_Trout Brown Trout Page] | *[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Brown_Trout Brown Trout Page] | ||

| + | *[[Natal Origins Project (NO)]] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 60: | Line 138: | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| − | *[https://www.nps.gov/ | + | *[https://www.nps.gov/glca/planyourvisit/brown-trout-harvest.htm#:~:text=The%20incentivized%20harvest%20begins%20on,mouth%20of%20the%20Paria%20River. NPS Brown Trout Incentivized Harvest ] |

| − | + | *[[Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction Project]] | |

| − | *Mainstem trout removal at the LCR | + | *Mainstem trout removal at the LCR (2003-2006) |

*[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Trout_Management_Flows Trout Management Flows] | *[http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Trout_Management_Flows Trout Management Flows] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |- | ||

| + | ! <h2 style="margin:0; background:#cedff2; font-size:120%; font-weight:bold; border:1px solid #a3b0bf; text-align:left; color:#000; padding:0.2em 0.4em;">[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/NNFC_EA_12-30-11.pdf 2011 Non-Native Fish Control EA] </h2> | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_A_SDM%20Report.pdf Appendix A: Non-native Fish Control SDM Report] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_B_SciencePlan.pdf Appendix B: Non-native Fish Control Science Plan] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_C_BA.pdf Appendix C: Non-native Fish Control BA] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_D_Supp.pdf Appendix D: Non-native Fish Control BA Supplement] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_E_BO.pdf Appendix E: Biological Opinion] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/FINAL%20NNFC%20EA%20with%20Appendices/Appendix_F_SHPO.pdf Appendix F: SHPO Letter] | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 69: | Line 159: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2022''' | ||

| + | *[[Media:2020-2021 NPS Bright Angel Creek Brown Trout Control Season Report.pdf| 2020-2021 NPS Bright Angel Creek Brown Trout Control Season Report ]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2019''' | ||

| + | *[https://doi.org/10.3368/le.95.3.435 Donovan et al., 2019, Safety in numbers--Cost-effective endangered species management for viable populations. Land Economics] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2018''' | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/18apr23/Attach_08.pdf Bright Angel Brown Trout Removal and Humpback Chub Translocations] | ||

'''2017''' | '''2017''' | ||

| + | *[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.01.032 Bair et al., 2018, Identifying cost-effective invasive species control to enhance endangered species populations in the Grand Canyon, USA: Biological Conservation ] | ||

*[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/17jan26/AR11_Bair.pdf Is Rainbow Trout Control Necessary, and if so, What is the Most cost-effective approach? ] | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/17jan26/AR11_Bair.pdf Is Rainbow Trout Control Necessary, and if so, What is the Most cost-effective approach? ] | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''2014''' |

| − | *[ | + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/progact/amp/twg/2014-01-30-twg-meeting/AR_Healy_NNFC_GRCA.pdf Non-native Fish Control in Tributaries: Grand Canyon National Park (Healy) ] |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

'''2013''' | '''2013''' | ||

*[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/13feb20/Attach_07b.pdf Humpback Chub and Non-native Fish Control Update ] | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/13feb20/Attach_07b.pdf Humpback Chub and Non-native Fish Control Update ] | ||

| − | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/ | + | |

| − | *[ | + | '''2012''' |

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12aug29/Attach_05c.pdf Non-native fish Control Implementation PPT] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/Attach_11a.pdf AIF Two Environmental Assessments Updates] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/12feb22/Attach_11c.pdf Non-Native Fish Control EA PPT] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/12feb02/Attach_02.pdf Final Biological Opinion on the Operation of Glen Canyon Dam Including High Flow Experiments and Non-Native Fish Control Memo] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/12feb02/Attach_05c.pdf Executive Summaries from the High-Flow Experiment EA and the Non-Native Fish Control EA] | ||

'''2011''' | '''2011''' | ||

*[[Media:Coggins 2011 Nonnative fish control CR GC.pdf| Coggins et al. 2011. Nonnative Fish Control in the Colorado River in Grand Canyon, Arizona: An Effective Program or Serendipitous Timing? Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 140: 2, 456 — 470]] | *[[Media:Coggins 2011 Nonnative fish control CR GC.pdf| Coggins et al. 2011. Nonnative Fish Control in the Colorado River in Grand Canyon, Arizona: An Effective Program or Serendipitous Timing? Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 140: 2, 456 — 470]] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/11aug24/Attach_11a.pdf USGS Fact Sheet: An Experiment to Control Nonnative Fish in the Colorado River, Grand Canyon, Arizona] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/11aug24/Attach_16.pdf AIF: Report on Two Environmental Assessments (EAs): Protocol for High-Flow Experimental Releases EA and Non-native Fish Control EA and PPTs] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2009''' | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/09sep29/Attach_06.pdf Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center Updates] | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/09aug12/Attach_05c.pdf Summary of 2008 Mechanical Removal Project PPT] | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2003''' | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/03jun30/Attach_07b.pdf Non-native Fish Removal Efforts in Grand Canyon: A Proposed Modification to Ongoing Activities] | ||

|- | |- | ||

Latest revision as of 17:42, 22 February 2022

|

|

Findings from the Natal Origins Project (NO) Project

|

| -- |

-- |

-- |

|---|

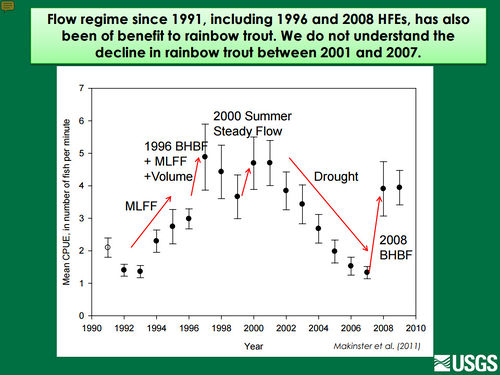

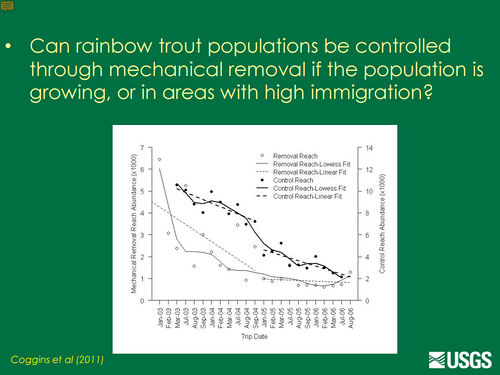

Removals at the Little Colorado RiverDuring 2003–2006, over 23,000 nonnative fish, including rainbow trout (19,020; 82 percent) and brown trout (479; 2 percent), were removed from a 9.4-mile reach of the Colorado River near the LCR confluence (Coggins and others, 2011). Concurrent with mechanical removal, mark-recapture studies within a control reach of river 20 miles upstream of the removal reach demonstrated a system-wide decline in both rainbow trout and brown trout that was unrelated to the fish removal effort. During this same period, a rapid shift in fish community composition was observed in the LCR reach (the mainstem Colorado River upstream and downstream of the LCR; see reach 2 in fig. 1), from one dominated by cold-water salmonids (>90 percent), to one dominated by native fishes and the nonnative fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) (>90 percent). Thus, our understanding of the efficacy of mechanical removal was confounded by an external systemic decline, particularly in 2005–2006 (Coggins and others, 2011). Another removal effort took place in 2009, with around 2,500 nonnative fishes removed from the LCR reach (Makinster and Avery, 2010). Subsequent electrofishing in the LCR reach showed that the number of rainbow trout and brown trout was higher after 2008 (fig. 4; Makinster and others, 2010), but the catch rate declined for rainbow trout and brown trout after 2014. The average catch per trip (based only on the first two passes of electrofishing to standardize across years) for rainbow trout was 209, 294, 460, 67, 18, and 56 between 2012 and 2017, and 2, 10, 5, 2, 0.3, and 2 for brown trout over the same period (C.J. Yackulic, GCMRC, written commun., April 3, 2018). [2]

Bright Angel Creek RemovalsA second effort to control nonnative fish, specifically brown trout, was implemented in 2002 in Bright Angel Creek. As recently as the 1970s, rainbow trout dominated the fish community in Bright Angel Creek and brown trout were rare (Minckley, 1978), despite this tributary having been stocked with brown trout, twice in 1930 and once in 1934. After the 1990s, however, brown trout became a predominant component of the fish community in the creek, and a corresponding decline in native fish such as speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) was observed (Otis, 1994). Bright Angel Creek is now a principal spawning site for brown trout, and an aggregation is found in the Colorado River near the confluence with Bright Angel Creek (fig. 3; Valdez and Ryel, 1995; Makinster and others, 2010). In an attempt to restore the native fish community of Bright Angel Creek and to reduce the threat of predation to humpback chub in the Colorado River, a program of mechanical removal of nonnative trout from Bright Angel Creek was implemented. From November 2002 to January 2003, a weir was operated near the creek mouth, which resulted in the capture of over 400 brown trout as part of an initial feasibility study (Leibfried and others, 2005; fig. 5). In 2006, the Bright Angel Creek Trout Reduction Project Environmental Assessment (EA) and Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI; National Park Service, 2006) identified goals and a strategy for reducing numbers of brown trout. This project was initiated in cooperation with the USFWS in 2006–2007 (National Park Service, 2006; Sponholtz and others, 2010) following the feasibility study. This effort was resumed in 2010 (Omana-Smith and others, 2012) following the 2008 and 2011 Biological Opinions on Operation of Glen Canyon Dam (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008 and 2011) that identified conservation measures to conduct trout reduction in Bright Angel Creek and to establish multiple self-sustaining populations of humpback chub in Grand Canyon tributaries (Valdez and others, 2000). [3] Current operations under the Bright Angel Creek trout control project were established through the NPS Comprehensive Fisheries Management Plan (CFMP; National Park Service, 2013a). From 2010–2012 trout reduction efforts included installation and operation of a weir and backpack electrofishing in the lower 2900 meters (m) of the creek (confluence to Phantom Creek; Omana-Smith and others, 2012). Beginning in fall of 2012, removal efforts were expanded to encompass the entire length of Bright Angel Creek (~16 kilometers [km]) and Roaring Springs (~1.5 km). The operation of the weir was extended from October through February to capture greater temporal variability in the trout spawn (Omana-Smith and others, 2012; National Park Service, 2013b). Electrofishing removal efforts, led by NPS and GCMRC, also occurred in the mainstem Colorado River in the Bright Angel Creek inflow in 2013 to 2016 (C. Nelson, USGS, oral commun., January 27, 2016). The brown trout removal effort in Bright Angel Creek proper has continued annually from 2010 to 2017 (Schelly and others, 2017). Across the most recent five seasons of removal, encompassing the entire Bright Angel Creek drainage, brown trout captures have declined steadily and considerably from 12,467 fish per year in 2012–13 to 4,902 in 2016–17, despite a similar level of effort each year. This decline has been most pronounced in age-2 and larger fish, with cohorts of age-1 fish produced in the previous season remaining fairly stable from year to year (fig. 6). A large cohort of age-0 fish was apparent in the winter of 2013–2014, perhaps a result of compensatory survival following removal of larger brown trout. Similar relative declines were seen in rainbow trout, which were also removed, while native fish abundance and upstream extent increased, particularly in speckled dace (B. Healy, NPS, written commun., March 5, 2018). [4] |

|