Difference between revisions of "Smallmouth Bass Page"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

[[File: SmallmouthCaptures.png|400px]] | [[File: SmallmouthCaptures.png|400px]] | ||

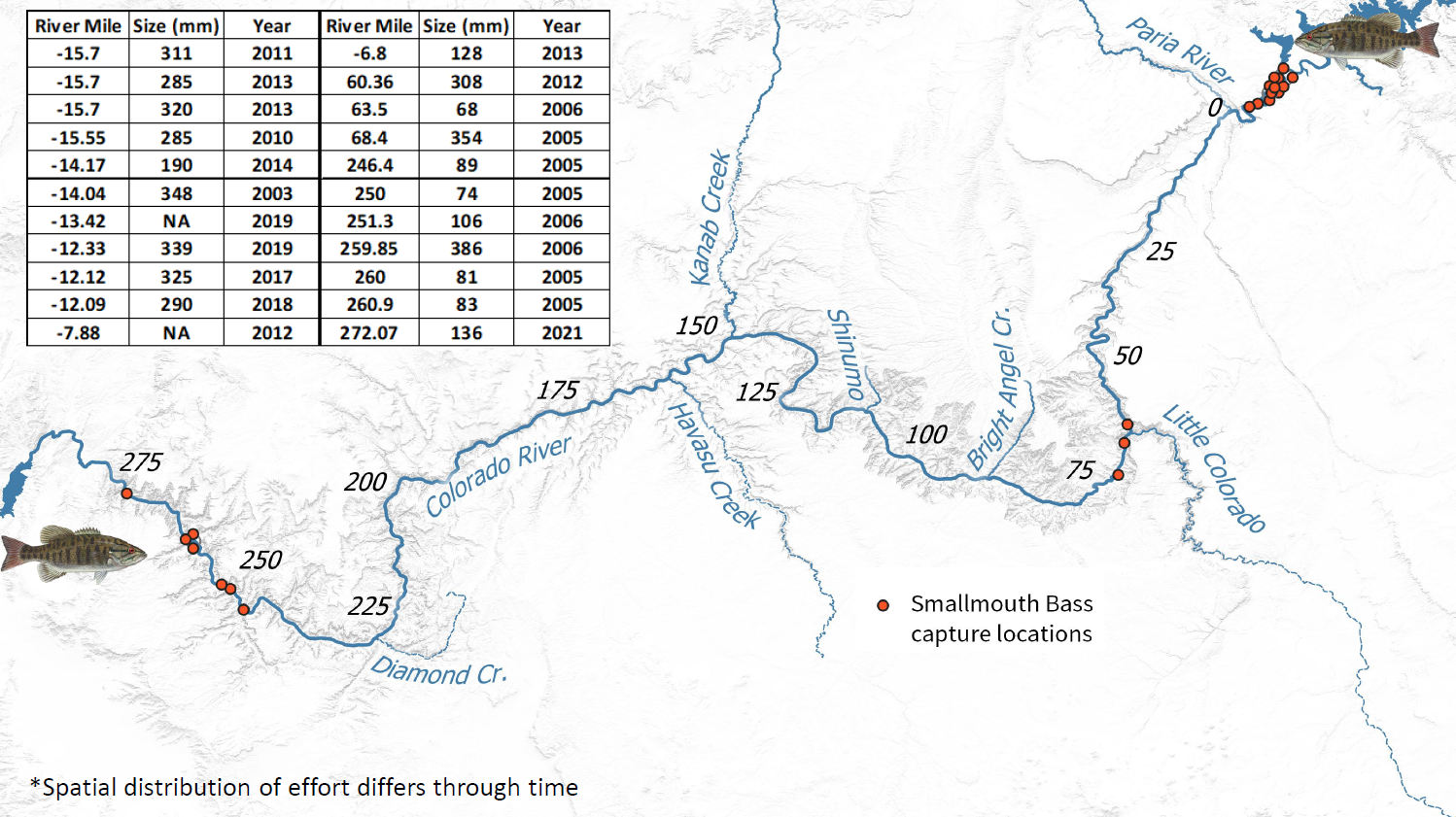

| − | Smallmouth bass have been sporadically captured below Glen Canyon Dam and in Grand Canyon since 2003. They were first introduced into Lake Powell in 1982 [https://wayneswords.net/threads/smallmouth-bass-history-in-lake-powell.1340/] and there are populations in ponds and lakes in the upper Little Colorado River as well as in Lake Mead. | + | Smallmouth bass have been sporadically captured below Glen Canyon Dam and in Grand Canyon since 2003. They were first introduced into Lake Powell in 1982 [https://wayneswords.net/threads/smallmouth-bass-history-in-lake-powell.1340/] and there are populations in ponds and lakes in the upper Little Colorado River as well as in Lake Mead. The following is a history written by Wayne Gustaveson. |

| + | |||

| + | Smallmouth Bass history in Lake Powell. <br> | ||

| + | Wayne Gustaveson, Feb 21, 2018 <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Lake Powell filled in 1980 after 17 years of constantly rising water levels. The consequences were dramatic. Largemouth bass and crappie had dominated the fishery in the filling reservoir. That changed, as the full reservoir began fluctuating up and down. Annual fluctuating water levels combined with daily wind and wave action uprooted brush in the fluctuation zone. The lake topped out at 3700 feet while lake level changed an average of 20 to 25 feet in any given year. Low water levels in the fall allowed some quick growing annual weeds to survive but perennial plants did not have enough time to become established before spring floods covered the ground once more. The shoreline now consisted of barren rock and sand instead of terrestrial desert vegetation that could be used by young bass and crappie as nursery cover when the flood covered the new brush each spring. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Monitoring the situation would not fix this problem as largemouth bass and crappie populations would crash as a result of inadequate nursery cover. The rapidly expanding striped bass population would incorrectly be blamed for the demise of largemouth bass and crappie. It was time for active management. My research indicated that smallmouth bass would reproduce and perform well in rocky substrate based on the simple principle that smallmouth fry hide in rocks when danger threatens. Largemouth bass and crappie fry must hide in brushy cover to ward off predation. Without brush, largemouth survival was poor but with two thousand miles of rocky shoreline smallmouth bass would thrive. This research was presented to the staff in Salt Lake who approved the concept. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is where it gets a bit tricky. Our striped bass hatchery in Big Water, Utah was out of production after striped bass natural reproduction was discovered in 1979. The hatchery was not used in 1980 or 1981. But we had a hatchery and the means to grow smallmouth bass. All that was needed was approval from Salt Lake, an adult bass brood source, and the ponds under my direction could turn out smallmouth bass fry in short order. The plans were approved and we went to work. Smallmouth bass were readily available in Flaming Gorge Reservoir. In spring 1982 we grabbed our fishing rods, caught 150 bass, and relocated them from the cold northern Utah border to the Southern Utah tropics. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It takes time to understand all the nuances of raising a new species of fish in a hatchery. The first year is often a learning experience where mistakes are made that lead to correct operations in the coming years. It was no different in 1982. We had not used the hatchery for two years and we had never raised smallmouth bass before, so the learning curve was steep. We made some mistakes but managed to produce about 10,000 bass fry when 10 times that many were expected. | ||

| + | |||

| + | My instructions from Salt Lake were to produce as many bass as possible. The highest priority was to place the first year’s progeny in Starvation Reservoir in Northern Utah. Second priority was to stock another lake in the north and third priority, if we had enough fish, would be Lake Powell. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Obviously with our meager production results there were not enough bass to stock all three lakes. The decision was made to place all the production from 1982 in Starvation Reservoir. The ponds were lowered and the two to three inch fingerlings were harvested over a three day period. It took a long time to harvest fish from our antiquated ponds that did not have catch basins. We had to lower the ponds individually and seine each pond a number of times to collect fish, which were then placed in a small 10x10 ft holding net until all the ponds were drained. On the third day the ponds were all harvested with all smallmouth fry placed in one holding net in one of the ponds. The stocking airplane was scheduled to arrive the next morning. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The plane landed at sunrise and we were dipping small bass out of the large holding net in the pond. Bass fry were dipped from the big net and placed in seven small holding nets. Then the small nets were suspended in a fish tank and rushed a half-mile up the hill to the flat road where the plane had landed. There were just enough fish in each net to fill one of the seven small, wet fish compartments on the plane. These 10,000 fish were extremely crowded in the plane’s holding tank. Time was critical to get them loaded and stocked as soon as possible. The flight took over two hours from Wahweap to Starvation so we worked fast and hard to make it happen. The plane was airborne again in less than an hour. | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the intense and focused effort to load fish in a timely manner it was time to relax and drain the fishpond. As the water went down it became obvious that the pond contained more than a few escapees. I looked at the net and saw that overnight maybe 500 but less than 1000 bass had exited our holding net out of one small hole. The plane was gone and it was not possible to put these fish on that flight. There were not enough fish to justify another expensive cross state flight to Starvation or to another lake in northern Utah. We had a few extra smallmouth bass. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1982 there were no cell phones, no Internet, and at the hatchery there was no telephone. We did not even have a hatchery building. We had a hatchery stocking truck and 500 extra fish. Someone needed to make a decision. My first option was to send the fish to Starvation. That goal had been met. The second option was to bring the plane back to put 500 fish in another lake. That was not economically feasible. Option three was to put 500 fish in the stocking truck and drop them off in Lake Powell on the way home. We could meet our third priority and take care of priority two next year when more fish would be raised. | ||

| + | |||

| + | It made sense, and it was economically practical. I stocked smallmouth bass in Lake Powell by driving the hatchery truck down Crosby Canyon road, opening the tube, and letting the fish flow down the pipe. It only took an hour and no extra funds. It was the right thing to do and I didn’t give it an extra thought. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In those days we had much more autonomy. We had to make decisions based on our directions and understanding. We communicated with our superiors by phone and by writing a monthly report, which was sent by US mail. My smallmouth stocking was completed before having access to the phone so I just included that incident in my monthly report and sent the letter. About three days later when the letter arrived in Salt Lake my phone rang shortly after the letter was opened. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The conversation was short. Don Andriano asked, “You did what?” I responded “Yes, I stocked 500 smallmouth bass in Lake Powell as it was the best choice of the options available to me at the time.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | Don asked, “Did you know that we did not have permission to do that?” I responded “No I was never told that, only that Lake Powell was third priority for stocking smallmouth bass this year.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | What was done was final. The conversation was over. I am sure Don had some explaining to do before the Colorado River Fish and Wildlife Council. In retrospect, asking forgiveness may have been a better choice than asking permission, which likely would never have been granted as I later learned with my proposal to introduce rainbow smelt into Lake Powell. | ||

| + | |||

| + | One result of my management action was satisfaction in knowing that smallmouth bass predictably performed magnificently along the rocky shoreline of the lake just as my research indicated they would. Anglers have caught millions of smallmouth bass over the past 30 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Another consequence was the threat of smallmouth bass predation on native species in the river running through the Grand Canyon. Fortunately, smallmouth did not populate the river as it was too cold for successful bass reproduction. Bass and native chubs and suckers need water temperatures above 60 degrees to successfully reproduce. The cold tailwater coming out of Lake Powell (46F) does not often provide adequate spawning temperature so bass and native fish do not reproduce in the mainstem Colorado River in most years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Largemouth and smallmouth bass have been good teammates in Lake Powell. As predicted, largemouth bass numbers crashed shortly after the lake filled. The lake over filled in 1983 covering brush along the shoreline once more. That gave largemouth an extra year and the population boomed until the lake stabilized and gradually declined from 1984 to 1992. When the brush was gone largemouth bass numbers plummeted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Drought-induced low lake levels in the early 90s allowed more brush to grow on the shoreline. Rising water in 1993 and 1994 covered the new brush and largemouth bass responded immediately as fry produced found nursery cover and survived at a high rate. That population peak lasted from 1994 to 1996 as a generation of bass completed their life cycle. The lake then stabilized again eliminating brush in the fluctuation zone. The next drought occurred at the same time as the Y2K scare that had folks wondering if computers would melt down as the new century was ushered in. From 2000 to 2004 Lake Powell steadily declined to a new low of 3555 MSL. New brush grew along the wet shoreline, as lake bottom became sandy beach once more. When the lake came back up from 2005 to 2008, largemouth bass again peaked in numbers and regained the high population level last seen when the lake filled and overfilled in 1981 to 1984. | ||

| + | |||

| + | I have included this technical discussion and graphics to show that largemouth bass respond to lake level and subsequent brush growth or elimination. Management of largemouth bass in Lake Powell would be possible if lake level could be controlled and regulated to allow new brush growth on demand. If there was a large red button on my desk that allowed me to control lake level, I could produce a consistent trophy-sized supply of largemouth bass and crappie at Lake Powell just by manipulating brush cover. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some have logically stated that striped bass predation has been responsible for the demise of largemouth in Lake Powell. The data indicates that the recent largemouth population boom from 2007 to 2011 occurred when the striped bass population was also abundantly strong. That seems impossible if striped bass predation was responsible for a decline in largemouth bass abundance. There is not a direct correlation or relationship between striped bass and largemouth populations. They are often separated without much contact by their affinity for different habitat types. Striped bass live in open water and prefer to feed on shad while largemouth live in shallow brushy habitat and feed on shad, sunfish and crayfish. | ||

'''2023''' <br> | '''2023''' <br> | ||

Latest revision as of 15:24, 3 January 2025

|

|

Smallmouth Bass (Micropterus dolomieui)The predatory threat of invasive and large-bodied piscivorous taxa such as smallmouth bass in the upper Colorado River basin is substantial. For example, based on results of a bioenergetics model, Johnson et al. (2008) ranked smallmouth bass as the most problematic invasive species because of their high abundance, habitat use that overlaps with most native fishes, and ability to consume a wide variety of life stages of native fishes (Bestgen et al. 2008). Expanded populations of piscivores such as smallmouth bass are a major impediment to conservation actions aimed at recovery efforts for the four endangered fishes in the upper Colorado River basin (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2002a, b, c, d). [1] |

| -- |

-- |

-- |

|---|

|

|