Difference between revisions of "Humpback Chub Page"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

|style="width:60%; font-size:120%;"| | |style="width:60%; font-size:120%;"| | ||

'''Description'''<br> | '''Description'''<br> | ||

| − | The [http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/general-information/the-fish/humpback-chub.html humpback chub (Gila cypha)] is an endangered, native | + | The [http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/general-information/the-fish/humpback-chub.html humpback chub (Gila cypha)] is an endangered, native endemic of the Colorado River that evolved around 3-5 million years ago. The pronounced hump behind its head gives this fish a striking, unusual appearance. It has an olive-colored back, silver sides, a white belly, small eyes and a long snout that overhangs its jaw. Like the Colorado pikeminnow and bonytail, the humpback chub is a member of the minnow family. |

The humpback chub is a relatively small fish by most standards – its maximum size is about 20 inches and 2.5 pounds. By minnow standards it is a big fish, though not like the giant of all minnows – the Colorado pikeminnow. Humpback chub can survive more than 30 years in the wild. It can spawn as young as 2 to 3 years of age during its March through July spawning season. | The humpback chub is a relatively small fish by most standards – its maximum size is about 20 inches and 2.5 pounds. By minnow standards it is a big fish, though not like the giant of all minnows – the Colorado pikeminnow. Humpback chub can survive more than 30 years in the wild. It can spawn as young as 2 to 3 years of age during its March through July spawning season. | ||

| − | Although the humpback chub does not have the swimming speed or strength of the Colorado pikeminnow, its body is uniquely formed to help it survive in its whitewater habitat. The hump that gives this fish its name acts as a stabilizer and a hydrodynamic foil that helps it maintain position. The humpback chub uses its large fins to “glide” | + | Although the humpback chub does not have the swimming speed or strength of the Colorado pikeminnow, its body is uniquely formed to help it survive in its whitewater habitat. The hump that gives this fish its name acts as a stabilizer and a hydrodynamic foil that helps it maintain position and also probably helped it escape predation by making it difficult to be swallowed by all but the largest pikeminnow. The humpback chub uses its large fins to “glide” in eddy complexes, feeding on insects that become trapped in pockets of slow-moving water. |

'''Status and distribution'''<br> | '''Status and distribution'''<br> | ||

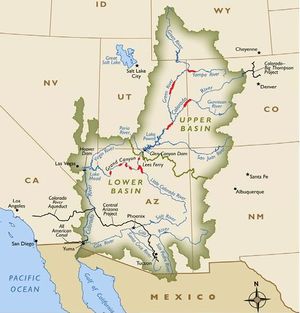

| − | The humpback chub was listed as endangered by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1967 and given full protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Historically, humpback chub | + | The humpback chub was listed as endangered by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1967 and given full protection under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. Historically, humpback chub were probably limited to the eddy complexes of several canyon reaches of the Colorado River and three of its tributaries: the Green and Yampa rivers in Colorado and Utah, and the Little Colorado River in Arizona. The species was first described in 1946. Before that time, few people ventured into these treacherous canyons – including fishery biologists. |

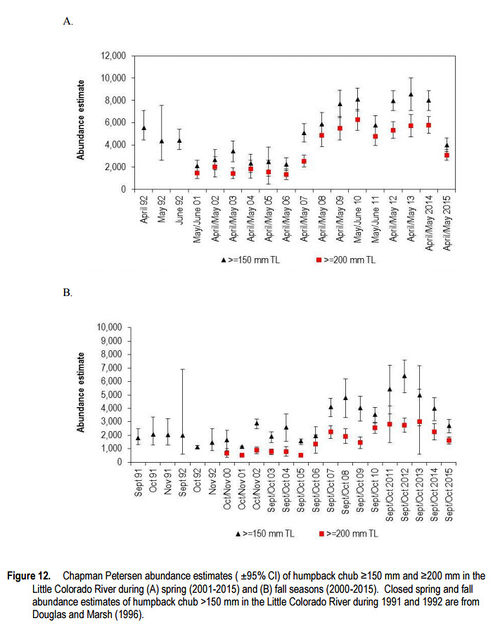

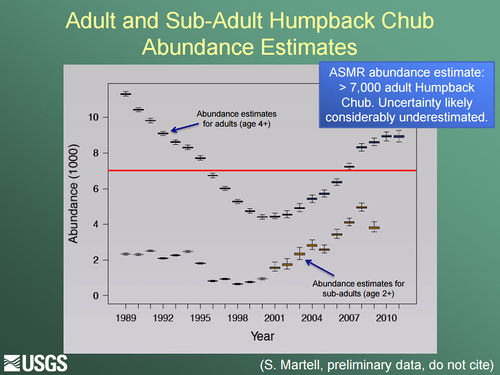

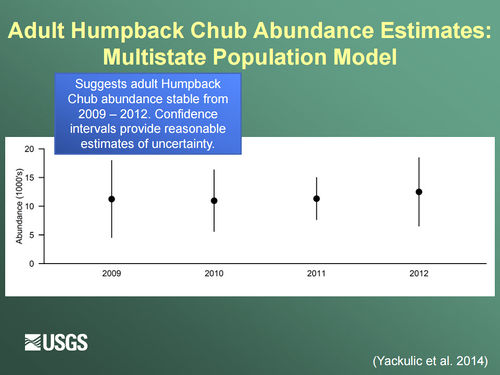

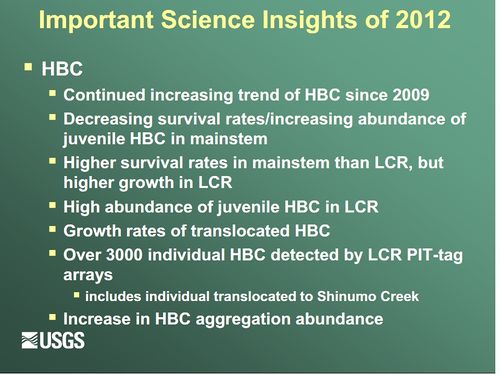

| − | Today, five self-sustaining populations of humpback chub occur in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Two to three thousand adults can occur in the Black Rocks and Westwater Canyon core population in the Colorado River near the Colorado/Utah border. Several hundred to more than 1,000 adults may occur in the Desolation/Gray Canyon core population in the Green River. Populations in Yampa and Cataract canyons are small, each consisting of up to a few hundred adults. | + | Today, five self-sustaining populations of humpback chub occur in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Two to three thousand adults can occur in the Black Rocks and Westwater Canyon core population in the Colorado River near the Colorado/Utah border. Several hundred to more than 1,000 adults may occur in the Desolation/Gray Canyon core population in the Green River. Populations in Yampa and Cataract canyons are small, each consisting of up to a few hundred adults. The largest population of humpback chub is found in the Grand Canyon -- primarily in the Little Colorado River (LCR) and its confluence with the main stem Colorado River. In 2009, the U.S. Geological Survey announced that this population increased by about 50 percent from 2001 to 2008 to between 6,000 and 10,000 adults. |

| − | + | One of the primary threats to humpback chub has been the proliferation of warm-water nonnative fish predators like smallmouth bass and northern pike. | |

|}<!-- | |}<!-- | ||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| − | 2016 | + | '''2016''' |

*[[Media:HBC Monitoring above Lower Atomizer Falls 2016 Trip Report.pdf| Spring 2016 Chute Falls humpback chub sampling trip report]] | *[[Media:HBC Monitoring above Lower Atomizer Falls 2016 Trip Report.pdf| Spring 2016 Chute Falls humpback chub sampling trip report]] | ||

*[[Media:Lower LCR Spring 2016 Trip Report.pdf| Spring 2016 Lower LCR humpback chub sampling trip report]] | *[[Media:Lower LCR Spring 2016 Trip Report.pdf| Spring 2016 Lower LCR humpback chub sampling trip report]] | ||

| Line 118: | Line 118: | ||

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/16jan26/documents/AR25_Young.pdf| Monitoring Humpback Chub Aggregations in the Mainstem, 1991-2015] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/16jan26/documents/AR25_Young.pdf| Monitoring Humpback Chub Aggregations in the Mainstem, 1991-2015] | ||

| − | 2015 | + | '''2015''' |

*[https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwY-Z2c3NTUGdXc2WHJOWkdBX3M/view| Havasu Creek Translocation Update] | *[https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BwY-Z2c3NTUGdXc2WHJOWkdBX3M/view| Havasu Creek Translocation Update] | ||

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/15feb25/Attach_05b.pdf| Native-nonnative Interactions; Factors Influencing Predation and Competition] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/15feb25/Attach_05b.pdf| Native-nonnative Interactions; Factors Influencing Predation and Competition] | ||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/15jan20/Attach_15.pdf| Biological Opinion Trigger Update: January 2015] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/15jan20/Attach_15.pdf| Biological Opinion Trigger Update: January 2015] | ||

| − | 2014 | + | '''2014''' |

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14oct28/Attach_14a.pdf| HBC Downlisting and Kanab Ambersnail Delisting] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14oct28/Attach_14a.pdf| HBC Downlisting and Kanab Ambersnail Delisting] | ||

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14oct28/Attach_11.pdf| 2014 Shinumo Creek Flood] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14oct28/Attach_11.pdf| 2014 Shinumo Creek Flood] | ||

| Line 134: | Line 134: | ||

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14jan30/AR_Yackulic_Results.pdf| Results from Colorado River Site and ongoing population modeling] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/14jan30/AR_Yackulic_Results.pdf| Results from Colorado River Site and ongoing population modeling] | ||

| − | 2013 | + | '''2013''' |

*[[Near Shore Ecology (NSE) Study]] of the fall steady flow test | *[[Near Shore Ecology (NSE) Study]] of the fall steady flow test | ||

*Dodrill, M. J. C. B. Yackulic, B. S. Gerig, W. E. Pine, III, J. Korman and C. Finch. 2014. Do management actions to restore rare habitat benefit native fish conservation? Distribution of juvenile native fish among shoreline habitats of the Colorado River. River Research and Applications. DOI 10.1002/rra/2842. | *Dodrill, M. J. C. B. Yackulic, B. S. Gerig, W. E. Pine, III, J. Korman and C. Finch. 2014. Do management actions to restore rare habitat benefit native fish conservation? Distribution of juvenile native fish among shoreline habitats of the Colorado River. River Research and Applications. DOI 10.1002/rra/2842. | ||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

*[http://wec.ufl.edu/floridarivers/NSE/Hayden%20et%20al.%202012.pdf Hayden, T. A., K. E. Limburg, and W. E. Pine, III. 2012. Using Otolith Chemistry Tags and Growth Patterns to Distinguish Movements and Provenance of Native Fish in Grand Canyon. River Research and Applications. DOI 10.1002/rra.2627] | *[http://wec.ufl.edu/floridarivers/NSE/Hayden%20et%20al.%202012.pdf Hayden, T. A., K. E. Limburg, and W. E. Pine, III. 2012. Using Otolith Chemistry Tags and Growth Patterns to Distinguish Movements and Provenance of Native Fish in Grand Canyon. River Research and Applications. DOI 10.1002/rra.2627] | ||

| − | 2011 | + | '''2011''' |

*[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/11aug24/Attach_06.pdf| GCMRC Update - Chub, Temperature, and Sediment] | *[http://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/amwg/mtgs/11aug24/Attach_06.pdf| GCMRC Update - Chub, Temperature, and Sediment] | ||

Revision as of 15:27, 18 July 2016

|

Description The humpback chub is a relatively small fish by most standards – its maximum size is about 20 inches and 2.5 pounds. By minnow standards it is a big fish, though not like the giant of all minnows – the Colorado pikeminnow. Humpback chub can survive more than 30 years in the wild. It can spawn as young as 2 to 3 years of age during its March through July spawning season. Although the humpback chub does not have the swimming speed or strength of the Colorado pikeminnow, its body is uniquely formed to help it survive in its whitewater habitat. The hump that gives this fish its name acts as a stabilizer and a hydrodynamic foil that helps it maintain position and also probably helped it escape predation by making it difficult to be swallowed by all but the largest pikeminnow. The humpback chub uses its large fins to “glide” in eddy complexes, feeding on insects that become trapped in pockets of slow-moving water.

Today, five self-sustaining populations of humpback chub occur in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Two to three thousand adults can occur in the Black Rocks and Westwater Canyon core population in the Colorado River near the Colorado/Utah border. Several hundred to more than 1,000 adults may occur in the Desolation/Gray Canyon core population in the Green River. Populations in Yampa and Cataract canyons are small, each consisting of up to a few hundred adults. The largest population of humpback chub is found in the Grand Canyon -- primarily in the Little Colorado River (LCR) and its confluence with the main stem Colorado River. In 2009, the U.S. Geological Survey announced that this population increased by about 50 percent from 2001 to 2008 to between 6,000 and 10,000 adults. One of the primary threats to humpback chub has been the proliferation of warm-water nonnative fish predators like smallmouth bass and northern pike. |

| --- | Fish Species of the Colorado River in Lower Glen Canyon and Grand Canyon | --- |

|---|