Is the slough a historical feature?

|

|

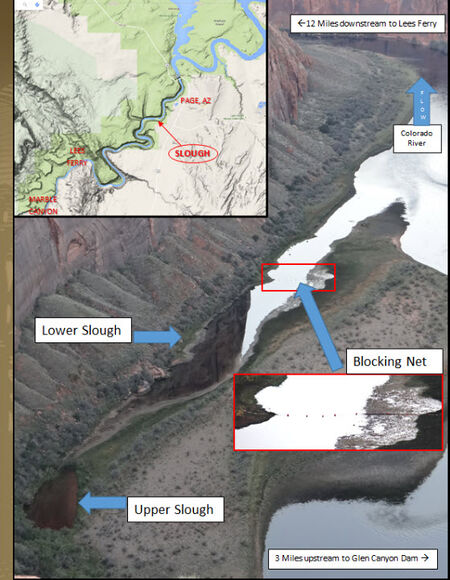

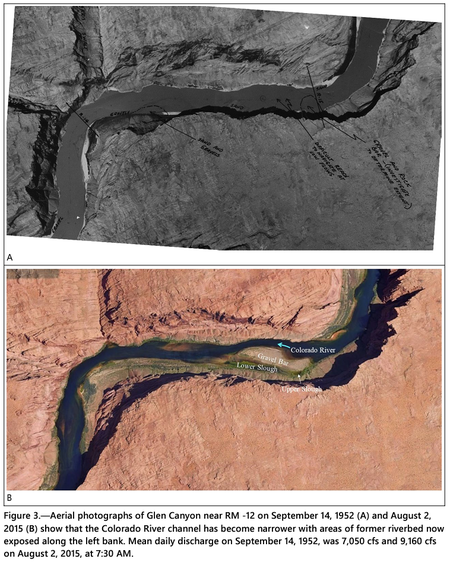

Following the closure of Glen Canyon Dam in 1963, Lake Powell began trapping sediment that resulted in erosion of the Colorado River channel through Glen Canyon creating a narrower and deeper channel (Pemberton, 1976, and Grams et al, 2007). Near RM -12, the channel thalweg has lowered 10 ft and the water surface elevation has lowered 5 ft subsequent to 1959 (Grams et al, 2007 see figure 9 of that report). Notations on a 1952 aerial photograph indicate that the left side of the river channel was shallow with a submerged “gravel and rock bar” at the upstream end and a sandbar at the downstream end (Figure 3A). In other words, the upper and lower slough as they exist today did not exist prior to the dam. After many years of streambed erosion, the channel became deeper along the right side of the canyon while the left side of the former riverbed became exposed as a high gravel bar. Depressions on the left side of the exposed gravel bar now function as the upper and lower sloughs (Figure 3B). [2]

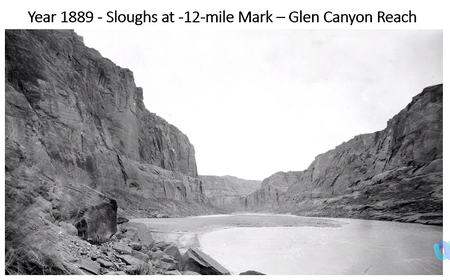

The 1889 photo, captured 74 years before 1963 dam completion, shows a sandbar and a distant backwater that have persisted in various forms during the past 135 years or longer. The bar is composed of sand with no vegetation, suggesting a more dynamic river with high spring season flows and summer monsoon flash floods, which at times flowed over the bar. The 2011 photo, captured 61 years after dam completion, shows the slough site with cobble and vegetation growth, suggesting a less dynamic river with less frequent flows of water over the bar. During the 135-year period, the general shape of the bar and lower slough backwater remain similar, even though river flows at times covered the entire slough and bar with high water flows. [3]

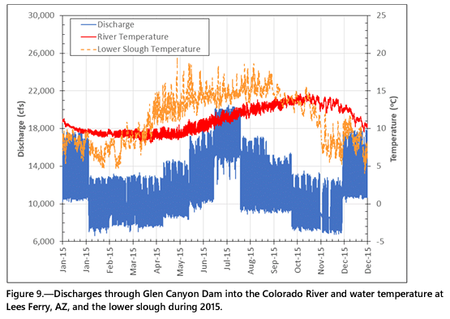

|

Slough Modification

|

|

1.2 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR PROPOSED ACTION

Purpose: The purpose of taking action is to compliment collaborative, interagency management strategies being implemented to prevent the successful reproduction of high-risk (predatory) warmwater nonnative fish, particularly smallmouth bass and green sunfish in the upper and lower sloughs at river mile -12, which has conditions favorable for nonnative fish spawning. The approach would seek to minimize negative effects on native species, restore natural functions or dynamics, and mitigate impacts, as necessary.

Need: The need is driven by increased levels of entrainment of high-risk nonnative warmwater species surviving passage through the Glen Canyon Dam due to lower Lake Powell elevations, the increased dam outflow temperatures in 2022 and 2023, the expectation that these conditions will occur in the future, and the resulting reproduction of predatory smallmouth bass and green sunfish, including in the river mile -12 upper and lower slough. Reducing nonnative fish reproduction at this site would help reduce the likelihood of their downstream expansion and establishment in Glen, Marble, and Grand Canyons.

Action is needed to disrupt or prevent the establishment of high-risk (predatory) warmwater nonnative fish in the proposed project area by limiting additional recruitment before the 2025 reproductive season and beyond. Warmwater nonnative fish threaten populations of the federally listed fish species humpback chub and razorback sucker and other native fish, amphibians, and invertebrates in Glen Canyon, Marble Canyon, and Grand Canyon. [4]

|

The Slough Spring

|

|

|

Links

|

|

|

Documents

|

|

|

Presentations and Papers

|

|

|

Rotenone Treatments

|

- November 2-6, 2015: rotenone treatment for green sunfish

- September 17-19, 2022: rotenone treatment for smallmouth bass

- August 25-28, 2023: herbicide treatment for smallmouth bass

|

Slough Temperatures

|

|

The slough is only exposed to the sun from February to November. The rest of the year the sun is behind the canyon rim.

- November-February: no sun

- April: 4 hours

- May: 11 hrs

- June-August: 11.5 hrs

- September: 4 hrs

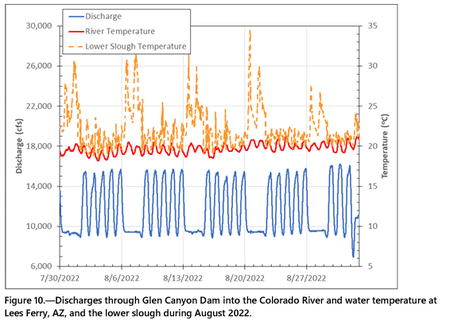

Upper slough water temperatures are more susceptible to seasonal fluctuations than the river. Water temperatures in the upper slough typically become even colder than the river water during the winter because there is not normally a surface water connection between the river and upper slough during this time of the year. The reverse pattern happens during the summer when the slough water temperatures warm with the air temperature. Discharge and temperature data from 2015 show that water temperatures in the lower slough vary with season and with river discharge (Figure 9). Water temperatures in the slough were colder than the river water during that year in January, February, much of March, November, and December. However, water temperatures in the lower slough were significantly warmer than the river channel during May, June, July, August, and September. Similar trends were observed in other abbreviated data sets provided by the National Park Service for 2013 through 2017, and 2022. Additionally, discharge and temperature data from August 2022 show that water temperatures in the lower slough were significantly warmer during weekends when the discharges are relatively steady, indicating that daily discharge fluctuations during the week exchange water with the lower slough and limit warming (Figure 10). [5]

|

The Slough Salamander

|

|

I wanted to follow up on yesterday’s discussion about tiger salamander in the -12L Slough and elsewhere in the Glen Canyon reach, and request access to some of the data we discussed.

I was quite amazed when, during a riparian restoration project at Leopard Frog Marsh (-9L) in March 2015, I first detected and photographed a large salamander at -9L Leopard Frog Marsh. It was, for me, a new vertebrate species in the Colorado River, and to my knowledge the only salamander ever reported from Colorado River corridor downstream from the Green River confluence. I include a picture of that individual with this email.

Upon finding that salamander, I immediately contacted the NPS at Glen Canyon and Dr. Charles Drost of the USGS to determine whether to collect it alive for genetic sampling. The advice I received was that it could be a native Ambystoma mauvortium stebbinsi and, while an interesting find, it would be best to release it, which I promptly did.

In finding it, I thought it most likely was an old individual of the widespread non-native subspecies Ambystoma mauvortium mauvortium that had escaped as a bait animal. Larval tiger salamanders used for fishing bait are called ‘water dogs’ or mud puppies. I thought this because: a) tiger salamanders can live to be 25 yr old; b) bait fishing was allowed in the tailwaters reach through the post-dam period until the 1990s; c) illegal bait fishing still likely occurs there.

I noted the fact that the individual was large and old, and that in many hundreds of hours over many years of studying and sampling backwaters in that reach and upper Grand Canyon, I had never detected salamander larvae. So, was this a real population, or just one or a few old bait bucket escapees? Further, I noted that the habitat at Leopard Frog Marsh (and also at the -12L Slough) does not contain all aspects of preferred habitat by the native salamander, which includes both wetland habitats that serve as breeding pools and upland coniferous forests that support the terrestrial life phases and traditional burrow sites.

With the discussion from yesterday’s TWG meeting, it appears that genetic information on the salamander has recently become available through the NPS. I am working with a team on a book on the hepetofauna of the Grand Canyon region, and therefore am quite interested in seeing the data from that genetics study, as I’m sure are many of our TWG colleagues. Having read through Scott Collins work on Ambystoma in Arizona, and spoken with him about northern Arizona tiger salamanders, the records we have for the native A. m. stebbinsi are from high elevation ponds and wetlands, particularly on the North Rim; however, the non-native bait subspecies, A. m. mauvortium has been widely introduced throughout the Southwest, including the northern half of the Arizona, and it may hybridize with the remaining native populations. In addition, the genetics data may tell us something about population structure, if any exists. Thus, high quality, peer-reviewed genetics data are needed to resolve the identity of the Colorado River individuals.

Also, there was mention yesterday of a 1950’s paper (perhaps by Stebbins or Lowe?) that considered there to be a potentially unique northern Arizona/southern Utah subspecies (separate from A. m. stebbinsi?). Both for the purposes of resolving this taxonomic issue and for reference for our book on Grand Canyon herpetofauna, While skeptical of that idea, I would very much appreciate the reference to that paper

Based on the information shared by Dr. Paul Grams concerning the length of time that the -12L Slough has supported stable wetlands, the absence of salamander detections at other locations on the river, and the lack of evidence of larval or young salamanders, I would be very surprised if the genetics indicated anything other than older adult A. m. mavortium or hybrid tiger salamander that has persisted there.

Thanks in advance for your attention to these requests,

Larry Stevens, PhD and Senior Ecologist Grand Canyon Wildlands Council and Director, Springs Stewardship Institute 414 North Humphries St. Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 USA (928) 440-3191 office larry@springstewardship.org SpringStewardshipInstitute.org

|

|