|

|

|

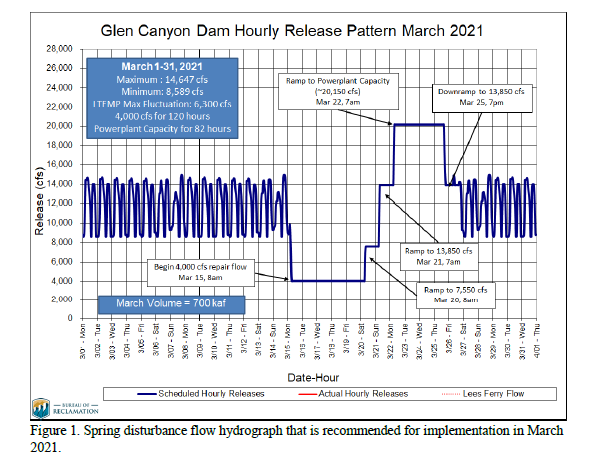

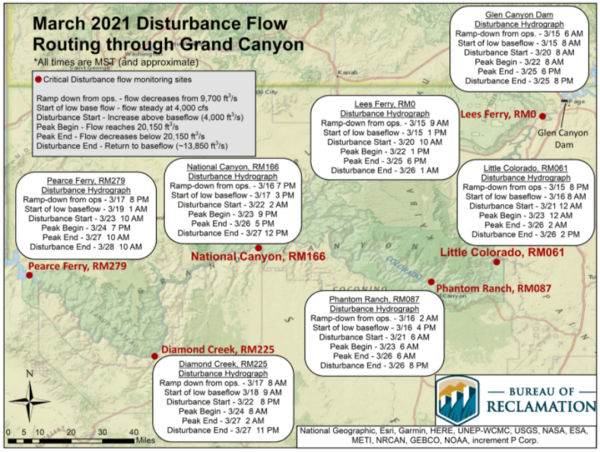

Glen Canyon Dam has altered ecological processes of the Colorado River in Grand Canyon. Before the dam was built, the Colorado River experienced seasonable variable flow rates, including springtime flooding events. These spring floods scoured the river bottom and enhanced natural processes that sustained the Colorado River ecosystem. Since the dam’s construction in 1963, springtime floods have been extremely rare and of low magnitude. Now, after more than 50 years of operation, the apron (underwater portion) of the Glen Canyon Dam requires maintenance. To facilitate this, releases from Glen Canyon Dam will be reduced to 4000 cubic feet per second (cfs), which is about one-third the average for March. This low flow will be immediately followed by a high flow disturbance which will consist of water releases of about 20,150 cfs. This combination of low and high flow disturbance is expected to enhance the natural processes that sustain the Colorado River ecosystem by mimicking springtime pre-dam flooding.[2]

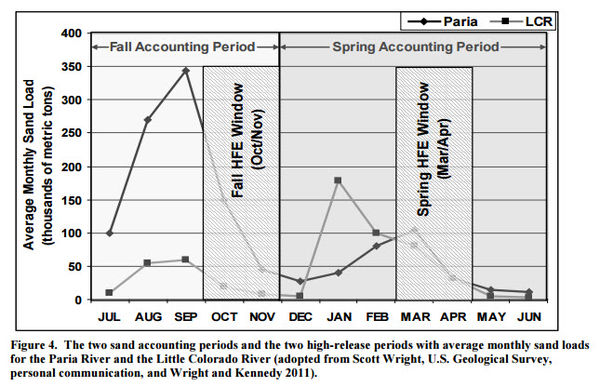

To test both spring and fall HFEs, the HFE protocol proposed using two sediment accounting periods.

These sediment accounting periods are used to track the quantity of new Paria River sand available for

building beaches in Marble Canyon during an HFE, and HFEs are only triggered if the quantity of new

sand is large. This sediment accounting approach to triggering HFEs, coupled with state-of-the-art

sediment monitoring (Topping and Wright 2016), eliminates the possibility of unintentionally scouring

sediment resources from Marble Canyon during HFEs. When the HFE protocol was first proposed, it was

estimated that sediment-triggered fall HFEs would occur approximately two out of every three years and

sediment-triggered spring HFEs would occur approximately once every three years (Wright and Kennedy

2011). [3]

Although Sediment-Triggered Spring HFEs and Proactive Spring HFEs are now possible, analysis of Paria

River discharge data indicates that Sediment-Triggered Spring HFEs may occur less frequently than

originally estimated (Grams and Topping 2018). Sediment accounting data available since the HFE

protocol was operationalized in 2012 bear this out. Specifically, since 2012 the sediment trigger for a fall

HFE has been reached 6 times (i.e., 2012-2016, 2018; no HFE occurred in 2015 owing to green sunfish)

while the sediment trigger for a spring HFE has never been reached (Grams and Topping 2020). Testing

of 5 fall HFEs over the past 8 years has benefitted sediment resources and reduced uncertainties

concerning sandbar response to HFEs in general (Figure 2). However, regular testing of fall HFEs since

2012 is also correlated with a growing population of brown trout in Lees Ferry (Runge and others 2018)

and critical uncertainties concerning the role of spring HFEs in achieving biological resource objectives

remain unanswered (Figure 2).

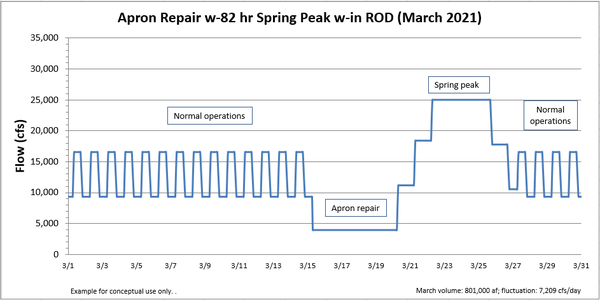

By May 2020, the FLAHG and GCMRC completed design of a conceptual hydrograph that included a high

spring release that was within power plant capacity. The FLAHG hydrograph capitalizes on a unique low

flow of 4,000 ft3 /s for 5 days, which is needed to conduct maintenance on the apron of Glen Canyon

Dam (see Figure 3). The FLAHG hydrograph proposes to follow this low flow disturbance with a high flow

disturbance that will culminate in a discharge of up to 25,000 ft3 /s for 82 hours. This combination of

desiccation at low flows followed by scour at high flows is hypothesized to disturb benthic habitats to a

much greater extent than either the low or high flows alone (Kennedy and others 2020). [4]

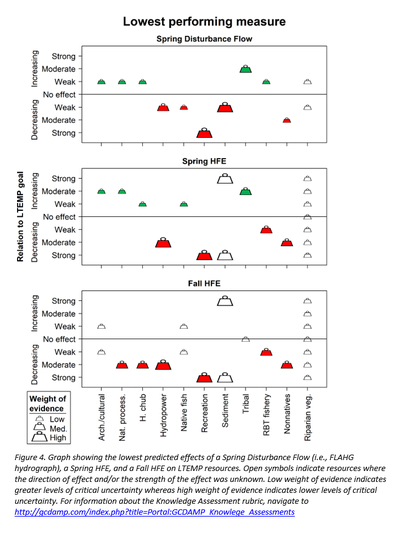

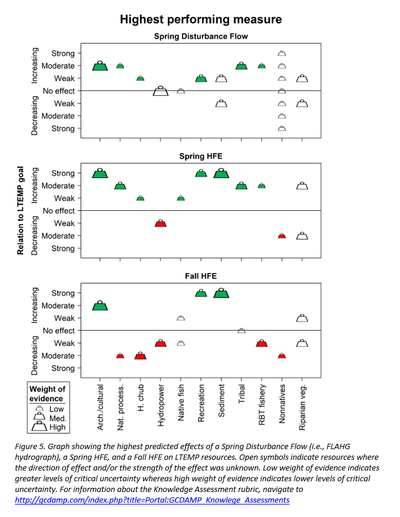

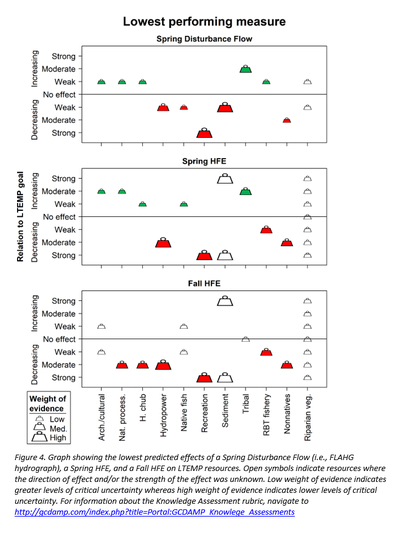

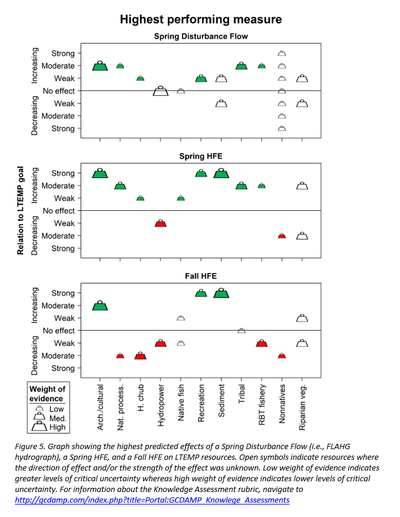

Below we present predicted effects of the FLAHG hydrograph on the 11 LTEMP Resource Goals using the

Knowledge Assessment rubric from 2019

(http://gcdamp.com/index.php?title=Portal:GCDAMP_Knowlege_Assessments). For comparison, and to

anchor predictions concerning the FLAHG hydrograph, we also used the Knowledge Assessment

framework to predict effects of Spring and Fall HFEs on LTEMP Resource Goals. To simplify analysis of

hydrograph impacts, the FLAHG narrowed consideration of testing this hydrograph to sometime in

March based on the following two main reasons: 1) both the 1996 and 2008 Spring HFEs also occurred in

March, which will simplify evaluation and comparison of new biological data that might be collected

around a FLAHG hydrograph to earlier data from those spring HFEs, and 2) a March test of the FLAHG

hydrograph will minimize adverse impacts of the low flow to Recreational Experience by avoiding the

start of the commercial river trip motor season in April.

Knowledge Assessment groups often evaluated multiple specific measures to capture all the facets of a

given LTEMP goal. For example, the goal for Rainbow Trout Fishery is, “Achieve a healthy high-quality

recreational rainbow trout fishery in GCNRA and reduce or eliminate downstream trout migration

consistent with NPS fish management and ESA compliance.” To capture both facets of this goal, the

Knowledge Assessment team considered two specific measures: rainbow trout abundance in Lees Ferry,

and rainbow trout abundance at the Little Colorado River confluence. The predicted resource responses

to a given action often varied, depending on which specific measure was considered. We capture this

variation in predictions by presenting bookend, “lowest performing” and “highest performing”,

scenarios gleaned from the assessments and their differing specific measures. Note that the assessment

summaries and graphs are based on detailed assessments for each resource that were performed by

multiple subject matter experts (see section V. Acknowledgements for a complete list of participants).

Those detailed assessments are contained in a spreadsheet for each resource that accompany this

document. The detailed resource assessments were based on consideration of peer-reviewed literature,

modelling, and other quantitative science as well as more qualitative expert opinions, similar to previous

Knowledge Assessments. [5]

|

|

|

Project Element O.1. Does Disturbance Timing Affect Food Base Response?

This element includes funding for tracking food base response to the FLAHG/GCRMC

hydrograph in Year 1 (Figure 1). Due to logistical constraints, we will focus our sampling efforts

in and around Lees Ferry. Specifically, we propose to sample aquatic insect drift intensively at

four time periods: just prior to the low flow associated with apron repair, during the low flow,

during the subsequent high flows after apron repair, and during the base flows immediately after

the high flow. Sampling would occur over the course of 1-2 weeks at 5-10 sites throughout Glen

Canyon and Upper Marble Canyon. Sites will be identical to our regular monitoring sites spaced

roughly equidistant from GCD (starting at River Mile [RM] -15) to the head of Badger Rapid

(RM 8), allowing us to contrast food web impacts above and below the Paria River confluence.

The objectives of this sampling are twofold:

- Quantify invertebrate export resulting from spring flow disturbance. Specifically, quantify the extent to which nonnative New Zealand mud snails are exported or suffer high mortality as a result of these flows, and the extent to which patterns of midge, blackfly, and Gammarus drift differ from baseline conditions in past spring seasons and during prior, fall HFEs.

- Quantify organic matter export resulting from drying during apron repair and subsequent flushing during high flows, which may have concomitant impacts on aquatic insect habitat and food resources.

Project Element O.2. Bank Erosion, Bed Sedimentation, and Channel Change in Western Grand Canyon

In order to address the above research questions, we intend to study channel response to dam

operations in a short (~1 to 3 km) study reach (to be selected) downstream from Quartermaster

Canyon. We will work with the Hualapai Tribe to select a specific reach that is critical for boat

navigation. In the first part of our analysis, we propose to use available remote sensing data sets

to document historical changes in bank and river channel morphology. The second part of the

analysis will include collection of repeat surveys of the riverbed within the selected study reach

before, during, and following a dam-released flow pulse. The repeat surveys will allow

quantification of the magnitude and spatial distribution of channel morphological change

associated with the flow pulse and the return to normal dam operations. This analysis will be

conducted by using the field data to develop a streamflow and sediment transport model for the

study reach. The model will allow evaluating bed response in a predictive framework to

determine whether there are systematic changes in bed elevation caused by dam operations.

Because similar issues exist upstream along the deltas of the Colorado and San Juan arms of

Lake Powell, this research project also could provide guidance for management of other large

reservoirs in the Colorado River Basin.

Project Element O.3. Aeolian Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

We

propose to conduct research during the FLAHG spring flow at a combined archaeological

dunefield-sand bar monitoring site from Project D.1 where NPS is also considering conducting

riparian vegetation removal through the LTEMP vegetation management project, which could

increase the aeolian transport of sand from the sandbar to adjacent archaeological site. We

propose to leverage the FLAHG flow to measure sand drying rates, change in exposed subaerial

sand, and aeolian sediment transport potential during the extended low flow of 4,000 ft3/s

and subsequent high flow at the study site.

Project Element O.4. Riparian Vegetation Physiological Response

We propose to select a subset of species from those listed in Project C.2 (Figure 5), depending on

availability of those species at accessible river sites. The species selected will represent both

flood tolerant and drought tolerant species and will likely include arrowweed (Pluchea sericea),

coyote willow (Salix exigua), Emory’s baccharis (Baccharis emoryi), tamarisk (Tamarix spp.),

Emory’s sedge (Carex emoryi), and available Juncus spp. The daily measurements will include

those of the mesocosm experiments: stomatal conductance, stem water potential, relative

humidity, leaf turgor, and soil moisture. Measurements will be collected daily starting two days

prior to the experimental flows through two days after.

The target location for this work will be in and around Lees Ferry. If, however, weather

conditions result in a late start to the spring growing season and the target species are unlikely to

be fully leafed out and active at the time of the FLAHG flows, we will relocate to the area near

Phantom Ranch. Plants will be active in that river segment during the FLAHG flows but are less

desirable simply due to logistics.

Project Element O.5. Mapping Aquatic Vegetation Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

We propose to use this unique opportunity (coupled with advances in Project Element E.2 in

TWP FY2021-23) to understand how a spring disturbance flow affects the dominant primary

producers in Glen Canyon, with a secondary objective of determining the scale at which we

might be able to do so. This would be designed as a before and after-impact study, with one trip

immediately prior to the low flow (e.g., late February or early March), one trip immediately after

the higher flow (e.g., late March or early April), and one trip in June to detect vegetation

response and recovery. Images from the June trip will be compared to baseline images from 2016

and 2019 that were taken in years lacking a spring disturbance flow. If we can detect a change in

aquatic vegetation cover and/or composition on a short-term scale (i.e., one season), then that

result will inform the frequency at which we should undergo aquatic vegetation surveys (Project

Element E.2). For example, if we can detect change within a season over multiple trips, this

method could be considered a sensitive tool for detecting vegetation community responses to

dam operations and would further our understanding of factors that drive primary production in

Glen Canyon (Project E).

Project Element O.6. Brown Trout Early Life Stage Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

While a low steady flow timed during peak emergence could improve short-term swim-up and

growth conditions for brown trout fry, we anticipate an energetic cost for newly emerged brown

trout fry during the spring disturbance flow. Therefore, we plan on collecting data during the

year of the spring disturbance flow and comparing results to a non-flow year using the methods

outlined in Project Element H.3, which will improve understanding of how spring flow

configurations may affect brown trout in their early life history stages. Results will be compared

to age-1 brown trout catch from the TRGD project in fall of Year 2 for comparison, which would

be an indicator of brown trout recruitment strength following the spring disturbance flow

(Project Element H.2).

Project Element O.7. Native Fish Movement in Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

We propose the use of sonic tags to track the responses of humpback

chub and flannelmouth sucker to the proposed spring disturbance flow. While rare, adult

razorback sucker will be included in this study if captured or detected on the remote Submersible

Ultrasonic Receiver (SUR) network, since the species also spawns in spring and may respond to

simulated flood hydrograph (USFWS, 2018). We propose targeting two study sites, one within

the JCM-west reach to economically align with ongoing studies (Project Elements G.5, G.6), and

one in the Lake Mead formation area below ~RM 235 that is accessible via up-runs from Pearce

Ferry. We propose to sonic tag approximately 35 adult fish per site, and USFWS will sonic tag

another 35 fish as a match, for a total of ~70. Approximately half the tags will be inserted into

adult flannelmouth sucker, the other half into humpback chub. If we capture any adult razorback

sucker, they will receive priority over the other two species since they are rare in the system. The

effort will benefit from an array of ~27 remote SURs already in place within Grand Canyon

distributed from the LCR to Pearce Ferry to passively track native fish movement. We will also

actively track fish at both sites as time and resources allow, combined with analysis of general

movement patterns at the JCM-west vs. JCM-east sites to refine mark-recapture modeling

(Project Elements G.3, G.6).

Project Element O.8. Do Disturbance Flows Significantly Impact Recreational Experience?

Surveys will be conducted to obtain information on recreationists’ preferences and economic

values associated with flow attributes specific to a spring disturbance flow experiment.

Consistent with past research of angler and whitewater boater’s flow preferences, the surveys

will be designed to elicit economic values using choice experiment instruments in addition to

investigation into other quantitative and qualitative metrics of recreationists’ preferences and

perspectives. Participants will be intercepted immediately prior, during, and following the spring

disturbance flow, differing from past recreational surveys (Bishop and others, 1987; Neher and

others, 2017), and respondents will either be interviewed on-site or sent a mail survey packet,

with a follow-up protocol for non-responders.

Project Element O.9. Are There Opportunities to Meet Hydropower and Energy Goals with Spring Disturbance Flows? (funded in N.1).

This project element is addressed in Project N. The objective of Project N is to identify,

coordinate, and collaborate on design, monitoring, and research opportunities associated with all

operational experiments at GCD to meet hydropower and energy resource objectives, as stated in

the LTEMP ROD (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2016b). The possibility of higher spring flow

experiments will be addressed in Project N. Funding for this element is included in the Project

N.1 budget.

Project Element O.10. Sandbar and Campsite Response to Spring Disturbance Flow (funded in B.1).

Because deposition at sandbars and associated campsite area increase is expected to be much

lower in response to the ~25,000 ft3

/s or lower pulse flow than occurs during sediment-enriched

fall HFEs, extensive field measurements of sandbars and campsites before and after the pulse

flow are not planned. Instead, evaluation of the sandbar and campsite response to the pulse flows

will rely on daily images from the network of remote cameras that is maintained as part of

project B.1. Funding for this element is included in the Project B.1 budget.

Project Element O.11. Decision Analysis

This project element will utilize the multi-criteria decision and value of information analysis that

was undertaken in the decision analysis to support development of the GCD LTEMP (Runge and

others, 2015). The fundamental resource goals and performance metrics will be utilized to

instruct the proposed monitoring and research in the individual project elements and in the

allocation of funding within and across project elements. A workshop in Year 2 will occur

following the implementation of the FLAHG hydrograph. The workshop will provide an

opportunity to summarize the FLAHG hydrograph results, evaluate trade-offs identified with the

spring disturbance flow, and present an overview of the decision process with respect to

prioritization of funding for monitoring and research related to this and other potential future

spring flow experiments.

Budget Justification

Funding in Year 1 for all project elements will be sought through the Experimental Management

Fund (C.5 Experimental Management Fund; see TWP FY2021-23) except for Project Element

O.11. Note that Reclamation retains decision-making authority for the allocation of funds from

the C.5 Experimental Management Fund. Also, requests to support Project O through the

Experimental Management Fund should be considered in context with other requests from the

Experimental Management Fund (i.e. including, but not limited to Projects A.4, B.6.1-5, and

J.3). Additionally, consideration of funding for Project O elements should be done in accordance

with the recommendation developed by the BAHG on October 8, 2020.

In Year 1 Project Element O.11 will seek funding from TWP carryover funds from prior years,

or through annual review of the TWP, or through other Reclamation considerations. Likewise,

in Year 2, funding for O.1 and O.2 will be sought from TWP carryover funds from prior years, or

through annual review of the TWP, or through other Reclamation considerations. Opportunities

to leverage external resources and support from Program partners will be considered and

explored by GCMRC and Reclamation for Year 2 funding. It should be noted that funding for a

third year of data analysis and modeling is required for Project Element O.2 in order for it to be

successfully completed; however, at this time a funding source has not been identified.

Three project elements have funding requests in Year 2; 1) $146,563 for O.1 to quantify food

base response to spring disturbance flows, 2) $161,959 for O.2 to identify whether dam

operations exacerbate or mitigate boat navigation challenges associated with bed-sediment

accumulation in the western Grand Canyon, and 3) $61,359 for O.11 to conduct decision

analysis. Year 2 funding totals include salary for short-term field technicians, travel and training,

operating expenses, and logistics. The remaining project elements (O.3-O.10) seek funding only

in Year 1. The proposed funding for these elements includes cooperator support, travel and

training, operating expenses, logistics, and salary for short-term field technician support.It should

be noted that most funding for GCMRC salaries involved in project elements O.3-O.10 is already

included in related project elements in Projects A through N in the TWP FY2021-23.

|

|

Links

|

|

|

Documents

|

|

|

Presentations and Papers

|

|

2023

2022

2021

2020

|

Process

|

AMWG Action Item (May 2019)

It was suggested that the TWG take up consideration of the remaining “HFE Assessment” action item, which reads, “A next step would be for GCMRC to identify experimental flow options that would consider high valued resources of concern to the GCDAMP (i.e., recreational beaches, aquatic food base, rainbow trout fishery, hydropower, humpback chub and other native fish, and cultural resource), fill critical data gaps, and reduce scientific uncertainties.” The AMWG did not object to the remaining action item passing from GCMRC to the TWG.

DOI Direction (August 2019)

Dr. Petty Guidance Memo – Page 3 – “In response to stakeholder input at recent AMWG meetings, the feasibility of conducting Spring High Flow Experiments (HFE), along with modeling for improvements and efficiencies that benefit resources including natural, cultural, recreational, and hydropower should be explored. As a potential starting point, I encourage you to consider opportunities to conduct higher spring releases within power plant capacity, along with spring HFEs that may be triggered under the current LTEMP Protocol”

TWG motion on the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Work Plan (June 2020)

The TWG recommends that the AMWG recommend for approval to the Secretary of Interior the Triennial Work Plan and Budget FY 2021-2023 as provided to the TWG on June 23, 2020 and as requested to be revised by the TWG during their meeting on June 23 and 24, 2020.

Revisions requested by the TWG on June 23 and 24, 2020:

- Include the GCMRC B.4 work element in the budget ($58,000 for first 2 years and $64,000 for year 3).

- Remove and/or reduce GCMRC D.2 (approximately $39,000 in year 1, $36,000 in year 2, and $54,000 in year 3) and GCMRC D.3 (approximately $28,000 in year 1, $29,000 in year 2, and $0 in year 3).

- Include Havasu Creek and LCR-mouth gage in GCMRC A.1 at 17,000/year.

- Please change GCMRC Project N verbiage (Pg 294) from “For example, modeling a change in ramp rates to maintain or improve the hydropower and recreational resource objectives is a possible application of GCMRC Project N.” to: “For example, modeling a change in ramp rates to improve the hydropower resource objective is a possible application of Project N.”

- In accordance with direction provided by the AMWG as described in the FLAHG charge, include a project and/or project element to support the FLAHG charge, and provide funding if necessary.

- Remove Reclamation B.4, TWG Chair reimbursement (25,000 for FY 2021)

- Propose AGFD and GCMRC look to integrate work efforts to allow for an additional TRGD site to be monitored. Cost estimate for going from 1 TRGD to 2 TRGD sites is approximately 67,000.

- Prioritize the use of available, unprogrammed and unspent funds from FY 2020, 2021 and 2022 towards funding GCMRC G.6 (JCM-West) in 2023.

AMWG motion on the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Work Plan (August 2020)

AMWG recommends to the Secretary of the Interior the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program Triennial Budget and Work Plan—Fiscal Years 2021-2023 (July 29, 2020 draft), subject to the following:

- Removal from GCMRC Project N the following verbiage:

"Past research into changes in regional energy costs attributed to alteration of GCD operations have shown that no changes occur in hourly prices (U.S. Department of Interior, 2016b). Specifically, hourly energy prices at the regional hub important to GCD (Palo Verde) remain approximately the same with variation in production of energy at GCD. In addition, the analysis of experiments is a short-run analysis, assuming that demand for energy is inelastic (demand does not change with small changes in prices) and surplus power capacity exists. Therefore, changes in $/MW and $/MWh are accurate representations of the changes in consumer and producer surplus when evaluating minor, short-run changes in GCD operations. However, long- run changes in the energy sector may lead to a different economic outcome and a more complete modeling approach would be required. The evaluation of GCD operation and long-run changes in the electricity sector such as the integration of renewable energy, repurposing of federal hydropower resources, or power system capacity expansion would require a significant increase in research scope."

- Consideration of GCMRC Project O is deferred, but will be included in the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Work Plan as a proposal to be considered for the Reclamation C.5 Experimental Management Fund, pending revisions to be made by GCMRC and the Bureau of Reclamation and review by the Technical Work Group. After consideration and if recommended by AMWG, a springtime disturbance flow will be planned to occur in coordination with Glen Canyon Dam apron repairs, to ensure sufficient time to integrate the information and learning about the importance of springtime high flows into the 2021-2023 TWP, subject to an evaluation of the resource conditions described in the LTEMP ROD.

- AMWG acknowledges and appreciates the effort to develop Project O in response to elements of the TWG Recommendation for the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Work Plan, consistent with guidance from the Secretary’s Designee (memo issued August 14, 2019), and in support of the Flow Ad Hoc Group charge. GCMRC is commended for their effort.

- AMWG members will submit written comments to GCMRC and Reclamation on Project O no later than Friday, September 4, 2020. GCMRC and Reclamation will make revisions based on comments received and will submit the revised Project O plan for TWG consideration by Wednesday, October 7, 2020, for discussion at the October 2020 TWG meeting. AMWG directs the TWG to review the revised Project O and to forward a revised Project O recommendation for AMWG consideration no later than Friday, October 30, 2020. The AMWG will act on the TWG recommendation no later than Friday, November 20, 2020.

FLAHG Recommendation to the TWG (September 2020)

The FLAHG, working with GCMRC, has identified a higher spring release within power plant capacity hydrograph that meets the requirements set forth by the LTEMP ROD and considers high value resources of concern to the GCDAMP (including recreational beaches, aquatic food base, rainbow trout fishery, hydropower, humpback chub and other native fish, cultural resources, and vegetation), fills critical data gaps, and helps to reduce scientific uncertainties. The FLAHG submits this hydrograph to the TWG for their consideration.

Finalization of the Predicted Effects to Resources Document (October 2020)

BAHG Recommendation to the TWG on Project O (October 2020)

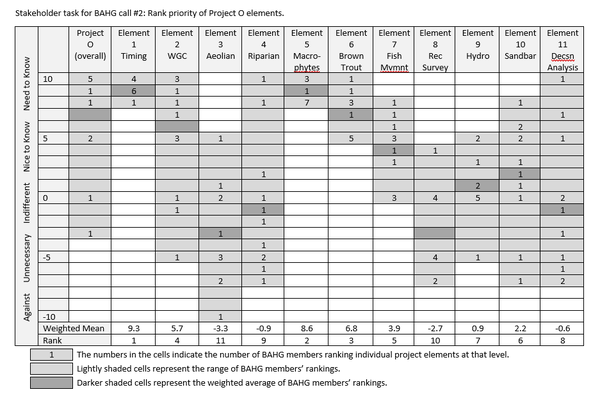

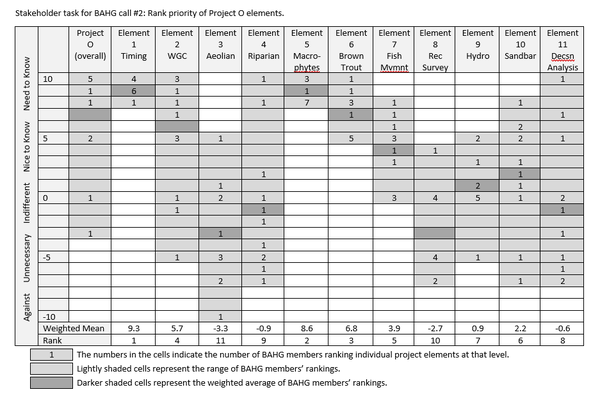

The BAHG expresses support for a Project O that evaluates the effects of the proposed FLAHG hydrograph. The BAHG recommends to the TWG the following elements outlined in Project O (July 2020 draft) be prioritized in the following rank order for funding a first year of work effort:

Tier 1 Projects (Weighted mean rankings from BAHG rating exercise: 9.3 and 8.6). The BAHG identified that these project elements are the most important for understanding the effects of the proposed FLAHG hydrograph.

- Project Element O.1. Does Disturbance Timing Affect Food Base Response?

- Project Element O.5. Mapping Aquatic Vegetation Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

Tier 2 Projects (Weighted mean rankings from BAHG rating exercise: 6.8, 5.7, and 3.9). The BAHG identified that these project elements are very important for understanding the effects of the proposed FLAHG hydrograph.

- Project Element O.6. Brown Trout Early Life Stage Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

- Project Element O.2. Bank Erosion, Bed Sedimentation, and Channel Change in Western Grand Canyon

- Project Element O.7. Native Fish Movement in Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

Tier 3 Projects (Weighted mean rankings from BAHG rating exercise: ≤ 0). The BAHG identified that these project elements are important for understanding effects of the proposed FLAHG hydrograph.

- Project Element O.11. Decision Analysis

- Project Element O.4. Riparian Vegetation Physiological Response

- Project Element O.8. Do Disturbance Flows Significantly Impact Recreational Experience?

- Project Element O.3. Aeolian Response to a Spring Pulse Flow

The BAHG acknowledges that the following projects are already funded in the TWP as Projects N.1 and B.1, thus a recommendation on rank priority is unnecessary:

- Project Element O.9. Are There Opportunities to Meet Hydropower and Energy Goals with Spring Disturbance Flows? (funded in N.1).

- Project Element O.10. Sandbar and Campsite Response to Spring Disturbance Flow (funded in B.1).

In our deliberations of Project O, the BAHG recommends that the Experimental Fund (Reclamation C.5) should not be used to support the following items and, to the extent that a proposed project element includes an item, that item should be removed from the project element:

- Multi-year commitments because the decision to use the Experimental Fund is made on a year-by-year basis;

- Monitoring for experiments or activities that occur with a level of regularity or certainty that would lend themselves to be planned for and funded through the TWP because this is counter to the intent of the Experimental Fund; and

- Salaries for positions lasting more than one year (i.e. anything more than a one-year term position or contract) because this may lead to unreasonable expectations of work security.

The BAHG also recommends that prioritizing elements in Project O for funding through the Experimental Fund should be made in context with other requests from the Experimental Fund and vice versa.

TWG motion on the Flow Ad Hoc Group (FLAHG) Hydrograph (October 2020)

The TWG recommends that the AMWG recommend to the Secretary of the Interior, to implement, when conditions warrant and consistent with the LTEMP protocol for implementing flow experiments, the spring disturbance flow hydrograph developed by the FLAHG in coordination with the GCMRC, as described in the FLAHG Predicted Effects document and associated presentations to the TWG on October 14, 2020.

TWG motion on Project O (October 2020)

The TWG recommends that the AMWG recommend to the Secretary of the Interior GCMRC’s “Project O” proposal, as provided to the TWG on October 7, 2020, for inclusion in the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Workplan, but with the following revisions and areas of emphasis:

- Reclamation retains decision-making authority for the allocation of funds from the C.5 Experimental Management Fund.

- Requests to support Project O through the Experimental Management Fund should be considered in context with other requests from the Experimental Management Fund (i.e. including, but not limited to Projects A.4, B.6.1-5, and J.3) and vice versa.

- Consideration of funding for Project O elements should be in accordance with the recommendation developed by the BAHG on October 8, 2020.

- Elements O.1 and O.2 – Funding requests for Year 2 should come from TWP carryover funds from prior years or through annual review of the TWP.

- Element O.11 – Funding requests for Year 1 and Year 2 could come from TWP carryover funds from prior years or through annual review of the TWP or other Reclamation considerations.

- References to specific years (e.g. FY2021) will be replaced with general references to Year 1 and Year 2 to accommodate uncertainty regarding implementation timing.

- Opportunities to leverage external resources and support from Program partners will be considered and explored by GCMRC and Reclamation.

AMWG motion on the Flow Ad Hoc Group (FLAHG) Hydrograph (November 2020)

The AMWG recommends to the Secretary of the Interior, to implement, when conditions warrant and consistent with the LTEMP protocol for implementing flow experiments, the spring disturbance flow hydrograph developed by the FLAHG in coordination with the GCMRC, as described in the FLAHG Predicted Effects document (dated October 6, 2020) and associated presentations to the AMWG on November 17, 2020.

AMWG motion on Project O (November 2020)

The AMWG recommends to the Secretary of the Interior GCMRC’s “Project O” proposal, as provided to the AMWG on November 10, 2020, for inclusion in the 2021-2023 Triennial Budget and Workplan, with the following areas of emphasis:

- Reclamation retains decision-making authority for the allocation of funds from the C.5 Experimental Management Fund.

- Requests to support Project O through the Experimental Management Fund should be considered in context with other requests from the Experimental Management Fund (i.e. including, but not limited to Projects A.4, B.6.1-5, andJ.3) and vice versa.

- Consideration of funding for Project O elements should be in accordance with the recommendation developed by the BAHG on October 8, 2020.

- Elements O.1 and O.2 – Funding requests for Year 2 should come from TWP carryover funds from prior years or through annual review of the TWP.

- Element O.11 – Funding requests for Year 1 and Year 2 could come from TWP carryover funds from prior years or through annual review of the TWP or other Reclamation considerations.

- Opportunities to leverage external resources and support from Program partners will be considered and explored by GCMRC and Reclamation.

|

|