Difference between revisions of "GCDAMP RAZU Fish"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Scientific Review Suggests Reclassification of the Razorback Sucker from Endangered to Threatened - October 4, 2018== | ||

| + | |||

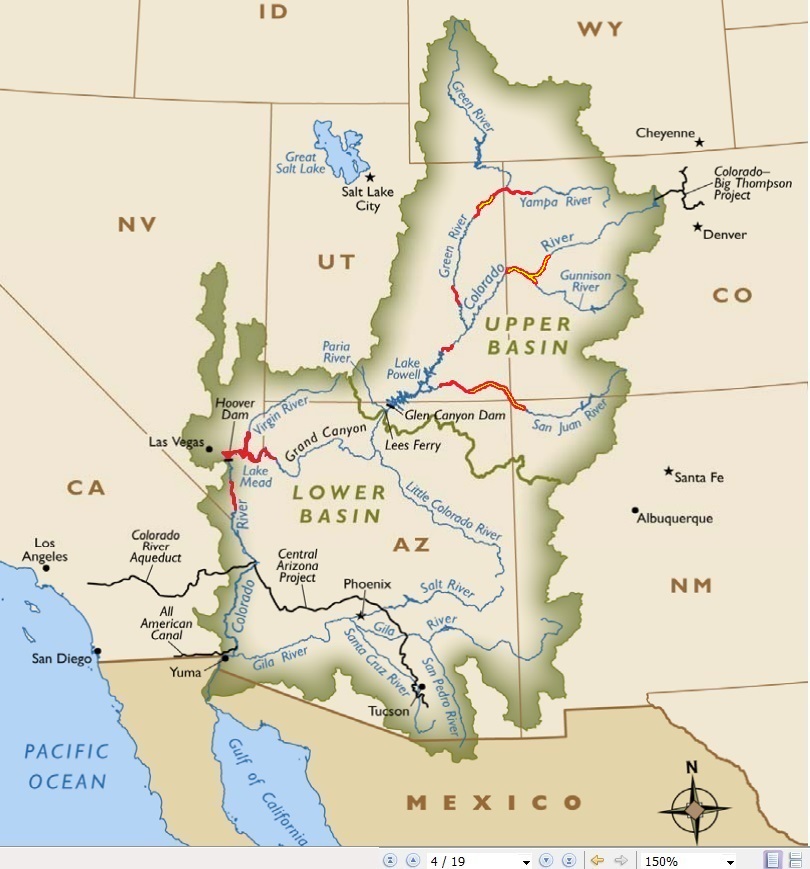

| + | DENVER —The razorback sucker, a native fish found in the Colorado River basin is making a comeback thanks to the work of conservation partnerships between the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), states, federal agencies, Tribes, industry and environmental groups. The Service recently completed a species status assessment (SSA) and a 5-year status review, utilizing the best available science, that concluded the current risk of extinction is low, such that the species is no longer in danger of extinction throughout all of its range. The SSA explained that large populations of adults have been re-established in the Colorado, Green, and San Juan Rivers. Populations are also present in Lake Powell, Lake Mead, Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu. As a result, in the future the Service proposes to reclassify the fish from endangered to threatened. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The razorback sucker is the second of the four native Colorado River fish to be proposed for a change in status from endangered to threatened this year. The humpback chub has also been proposed for reclassification. The recovery success of these two fish would not have been possible without the strong partnerships and conservation efforts all along the river. | ||

| + | |||

| + | “Our partners along the Colorado River have restored flow, created habitat, removed nonnative predators, and reestablished populations across these species range,” said Tom Chart, Director of the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program. “These partnerships have improved conditions, proving long-term commitments are a key component to recovery.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | The razorback sucker was first documented in the Colorado River system in 1861 and historically occupied an area from Wyoming to Mexico, often travelling hundreds of miles in a single year. The species gets its name from the bony keel behind its head, which helps it stay put when flows increase. Razorback sucker are part of the lake sucker family, preferring low-velocity habitats, in either backwaters, floodplains or reservoirs and evolved in an ecosystem with one large-bodied predator: the Colorado pikeminnow. Young razorback sucker have few defense mechanisms, making them vulnerable to predation , especially from toothed nonnative predators. Changes in river flows and introduction of nonnative fish caused dramatic population declines. Thanks to intense management efforts, razorback sucker have made a remarkable comeback, especially in the Green and Colorado rivers. In the Green River in the mid-1990’s, the number of adults captured in a year could be counted on one hand; today, the population has rebounded to over 30,000 adults. The large populations are the result of successful hatchery programs. Stocked fish not only survive in the wild, but migrate, colonize new areas, return to historic spawning bars, and produce viable young. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although this native fish is making a big step toward recovery, continued management efforts are needed to help the species cross the final threshold of being able to survive in sufficient numbers to reach adulthood. The Lake Mead population is the only population where juvenile fish routinely grow up into adults. All other populations are maintained through stocking efforts as the young are eaten by nonnative fish before they reach adulthood. Scientists are hard at work to determine the best ways to encourage survival of juveniles to naturally sustain the population. One wetland along the Green River managed for razorback sucker has produced over 2,000 young-of-year individuals in the past five years, the first substantial number of juveniles seen in over 30 years in the upper basin. | ||

| + | |||

| + | State, tribal, federal, and private stakeholders work together via the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, the San Juan River Recovery Implementation Program, and the Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Partnership to stock fish, create habitat, and continue monitoring programs to reduce threats to this species’ recovery. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In the 5-year review, the Service also recommends that the species recovery plan be revised to incorporate the best available scientific information on the species needs and actions that will eventually allow the Service to delist razorback sucker. Efforts to propose reclassification and to revise the recovery plan will be ongoing in the coming year. The proposed reclassification rule and the revised recovery plan will be made available for public comment in the future. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ---- | ||

*Larvae collected as far upstream as Havasu Creek [https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/18jan25/AR19.pdf] | *Larvae collected as far upstream as Havasu Creek [https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/amp/twg/mtgs/18jan25/AR19.pdf] | ||

| Line 138: | Line 156: | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| + | *[http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/documents-publications/foundational-documents/recoverygoals/Razorbacksucker%20SSA%20FINAL%20Aug%202018.pdf 2018 Razorback Sucker Species Status Assessment] | ||

| + | *[http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/documents-publications/foundational-documents/recoverygoals/2018_Razorback_sucker_5-year_Final.pdf 2018 Razorback Sucker 5-Year Review] | ||

*[http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/documents-publications/foundational-documents/recoverygoals/RBS5-yearStatusReview.pdf 2012 Razorback Sucker 5-Year Review] | *[http://www.coloradoriverrecovery.org/documents-publications/foundational-documents/recoverygoals/RBS5-yearStatusReview.pdf 2012 Razorback Sucker 5-Year Review] | ||

*[https://www.fws.gov/southwest/sjrip/pdf/DOC_Recovery_Goals_Razorback_sucker_2002.pdf?bcsi_scan_16614fa24ff8c4a5=0&bcsi_scan_filename=DOC_Recovery_Goals_Razorback_sucker_2002.pdf 2002 Razorback Sucker Recovery Goals] | *[https://www.fws.gov/southwest/sjrip/pdf/DOC_Recovery_Goals_Razorback_sucker_2002.pdf?bcsi_scan_16614fa24ff8c4a5=0&bcsi_scan_filename=DOC_Recovery_Goals_Razorback_sucker_2002.pdf 2002 Razorback Sucker Recovery Goals] | ||

Revision as of 09:11, 5 October 2018

|

|

Razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus)Three to 5 million years ago, a unique-looking fish with a sharp-edged hump “razorback” behind its head swam the Colorado River and its tributaries. The razorback sucker is an endangered, native fish of the Colorado River and the only member of the genus Xyrauchen. It has a dark, brownish-green upper body with a yellow to white-colored belly and an abrupt, bony hump on its back shaped like an upside-down boat keel. One of the largest suckers in North America, the razorback sucker can grow to 3 feet in length and can live for more than 40 years. Razorback sucker can reproduce at 3 to 4 years of age. Depending on water temperature, spawning can occur as early as November or as late as June. In the Upper Colorado River Basin razorback sucker typically spawn between mid-April and mid-June. Razorback sucker eat insects, plankton, and plant matter on the bottom of the river. To complete its life cycle, the razorback sucker moves between adult, spawning, and nursery habitats. Spawning occurs during high spring flows when razorback sucker migrate to cobble bars to lay their eggs. Larvae drift from the spawning areas and enter backwaters or floodplain wetlands that provide a nursery environment with quiet, warm, and shallow water. Research shows that young razorback sucker can remain in floodplain wetlands where they grow to adult size. As they mature, razorback sucker leave the wetlands in search of deep eddies and backwaters where they remain relatively sedentary, staying mostly in quiet water near the shore. In the spring, razorback sucker return to the spawning bar, often quite a long distance away, to begin the life cycle again.[1] Razorback suckers in Grand CanyonThe razorback sucker was thought to be extirpated, or locally extinct, from Grand Canyon until 2012 when several adult razorback suckers were captured in the western Grand Canyon during surveying work. Prior to these occurrences, razorback suckers were last found in Grand Canyon more than 20 years ago. Recently, they have been found spawning in the Colorado River inflow at the upper end of Lake Mead. The National Park Service is currently planning studies to determine the status of the species in Grand Canyon. Prior to the constructions of dams on the Colorado River and other human-caused alternations to their habitat, razorback suckers were widely distributed in the Colorado River and its major tributaries, and were typically found in calm flat-water reaches. There are at least ten historical records of razorback suckers caught in Grand Canyon, including a specimen caught in Bright Angel Creek in 1944. Today, the largest population, and possibly only population of wild reproducing razorback suckers, is in Lake Mead. The species was listed as endangered in 1991. Critical habitat, including all of Grand Canyon National Park, for the species was determined in 1994.[2] |

| Online training |

Fish Species of the Colorado River in Lower Glen Canyon and Grand Canyon |

Fish photos, information, and maps |

|---|

|

|