Difference between revisions of "FOOD BASE"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 235: | Line 235: | ||

Fish occupying warmer water have higher metabolic demands than individuals in cooler water, and if these demands increase concurrently with a seasonal decline in prey availability, then growth rates may be reduced. [http://wec.ufl.edu/floridarivers/NSE/Finch%20RRA%20HBC%20Growth%20NSE.pdf] | Fish occupying warmer water have higher metabolic demands than individuals in cooler water, and if these demands increase concurrently with a seasonal decline in prey availability, then growth rates may be reduced. [http://wec.ufl.edu/floridarivers/NSE/Finch%20RRA%20HBC%20Growth%20NSE.pdf] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

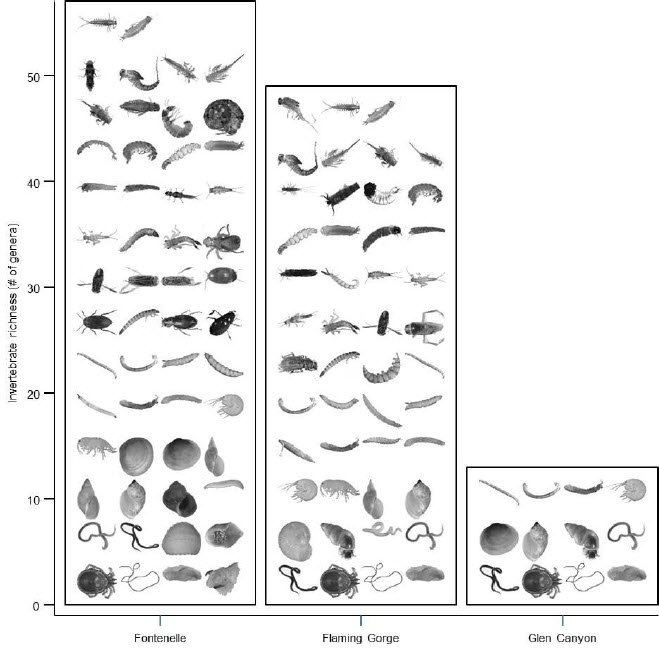

===Translocation of aquatic macroinvertebrates to the Glen Canyon tailwater=== | ===Translocation of aquatic macroinvertebrates to the Glen Canyon tailwater=== | ||

Notably, several species of cold-tolerant nonnative invertebrates were intentionally introduced into the Colorado River after Glen Canyon Dam was closed in 1963. Altogether 10,000 immature mayflies were secured from a commercial source in Minnesota and released at three sites in the Lees Ferry reach. Also, 10,000 snails, 5,000 leeches, and thousands of insects representing at least 10 families were transported from the San Juan River in New Mexico to the river near Lees Ferry. In addition, 50,000 “scuds” (Gammarus lacustris) were introduced into Bright Angel Creek in 1932 and at Lees Ferry and below the dam in 1968, in addition to 2,000 crayfish taken from the LCR near Springerville, AZ. Gammarus lacustris has thrived in the cold, clear reaches below the dam, but the fate of the other introduced species is unknown. [https://www.nap.edu/read/1832/chapter/8#114 (Blinn and Cole 1991)] | Notably, several species of cold-tolerant nonnative invertebrates were intentionally introduced into the Colorado River after Glen Canyon Dam was closed in 1963. Altogether 10,000 immature mayflies were secured from a commercial source in Minnesota and released at three sites in the Lees Ferry reach. Also, 10,000 snails, 5,000 leeches, and thousands of insects representing at least 10 families were transported from the San Juan River in New Mexico to the river near Lees Ferry. In addition, 50,000 “scuds” (Gammarus lacustris) were introduced into Bright Angel Creek in 1932 and at Lees Ferry and below the dam in 1968, in addition to 2,000 crayfish taken from the LCR near Springerville, AZ. Gammarus lacustris has thrived in the cold, clear reaches below the dam, but the fate of the other introduced species is unknown. [https://www.nap.edu/read/1832/chapter/8#114 (Blinn and Cole 1991)] | ||

| + | ---- | ||

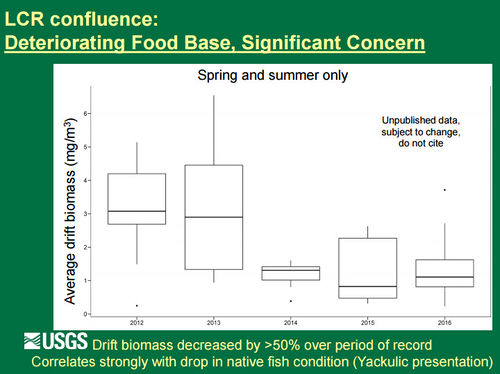

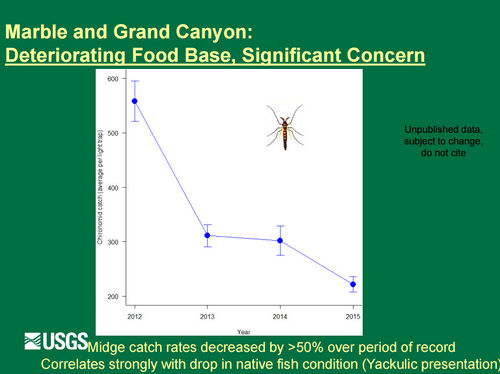

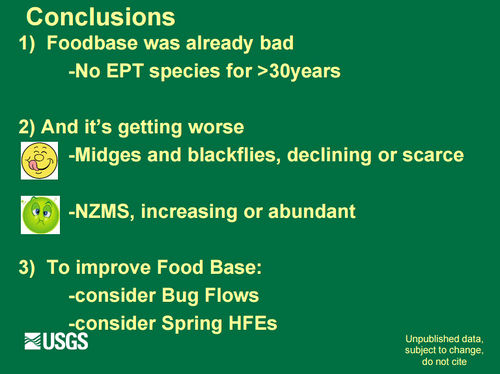

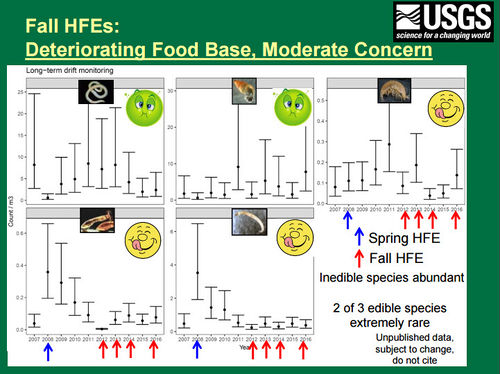

| + | *Gammarus, blackflies, and midges fuel fish production below Glen Canyon Dam. | ||

| + | *Blackflies and midges respond positively to spring HFE's. Gammarus show little response to fall or spring HFEs. | ||

| + | *Mud Snails were introduced below Glen Canyon Dam around 1995. | ||

| + | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 13:44, 6 June 2019

|

|

Aquatic Food Base monitoring below Glen Canyon Dam and into Grand CanyonAquatic insects live in the water as larvae most of their lives, then emerge onto land for a brief period as winged adults. Sampling these emerged adults on land is therefore a useful tool for understanding the condition of the aquatic insect population that is in the water, particularly in large rivers where sampling the larvae on the river bed is impractical. Our group uses a variety of methods for collecting these emergent insects, which we sample principally in the Colorado River in Glen, Marble, and Grand Canyons and also in the Little Colorado River. Aquatic insects have a terrestrial, winged adult life stage in which they leave the water and fly onto land in order to find a mate and reproduce. Sampling insects at this terrestrial, adult life stage, rather than the more traditional larval, aquatic life stage, allows us to understand aquatic insect population patterns in ecosystems, such as large rivers, where sampling the aquatic larvae directly is unsafe or impractical. Our group samples these emergent adult insects primarily using sticky traps, a method we developed in-house. In the Little Colorado River, we are using these samples to understand the patterns of aquatic insect abundance throughout a river segment that is critically important to an endangered fish, the humpback chub (Gila cypha). Additionally, we collect samples monthly from Lees Ferry on the Colorado River downstream of Glen Canyon Dam to better understand patterns of food availability for recreationally-important rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). We also deploy traps throughout the Colorado River in Grand Canyon to better understand patterns of insect movement in and out of tributaries, and to describe how insect abundance varies throughout this > 250 mile stretch of river and in response to operations from Glen Canyon Dam. Sticky trap-based results from the Little Colorado River have underscored how aquatic insect abundance may be driving spatial patterns of humpback chub density and growth that are observed by cooperators at the US Fish and Wildlife Service, Arizona Game and Fish Department, and USGS. In Lees Ferry, seasonal patterns of emergent adult aquatic insects also correlate well with observed patterns of rainbow trout growth, with peaks in spring, and very low densities in winter. Thus, monitoring of insect abundance is a useful, early indicator of ecosystem health that can foretell future changes in fish population health and abundance. [1] Desired Future Condition for the Aquatic Food BaseThe aquatic food base will sustainably support viable populations of desired species at all trophic levels. Assure that an adequate, diverse, productive aquatic foodbase exists for fish and other aquatic and terrestrial species that depend on those food resources. |

| EPT as Biologic Indicators of Stream Condition |

Algae and Aquatic Macrophytes |

Aquatic Macroinvertebrates |

|---|