Updates

|

|

|

Causal factors for loss of campsite area

|

|

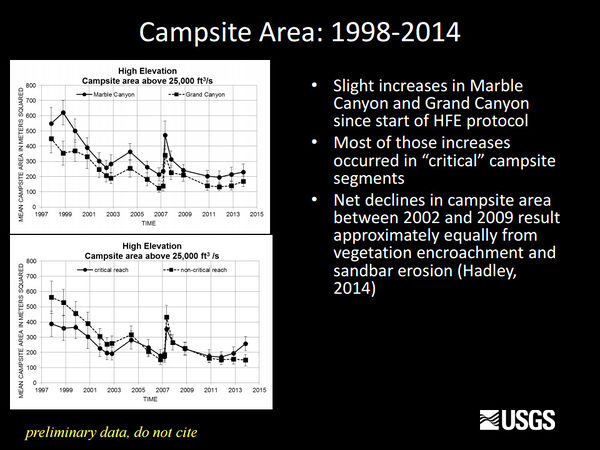

There were two primary drivers responsible for the net loss in campsite area — (1) increases and decreases in campsite area as a result of deposition and erosion associated with controlled floods and regular dam operations and (2) long-term declines in campsite area due to vegetation encroachment. Gains and losses in campsite area associated with topographic change can cancel each other out, whereas vegetation change, for the most part, only leads to losses in campsite area. In terms of net change, vegetation encroachment contributed to 47 percent of the overall net loss in campsite area, and topographic change contributed to 53 percent of the overall net loss in campsite area.

Controlled floods can lead to increases in campsite area and are currently the only management strategy used to improve campsites along the Colorado River corridor. However, erosion of flood-deposited sandbars during normal dam operations following controlled floods causes these increases in campsite area to be short lived. At the same time, vegetation cover continues to increase, resulting in the progressive decline of campsite area.

One potential strategy to increase campsite area more often is more frequent implementation of controlled floods to build sandbars. This strategy was initiated by the Bureau of Reclamation in 2012 by the adoption of a high-flow experimental protocol. This protocol allows for the implementation of a controlled flood every year, provided there is sufficient sand supplied by the Paria River (Bureau of Reclamation, 2012). Preliminary findings indicate that the protocol is resulting in larger sandbars (Grams and others, 2015). However, there is not always a direct correlation between increases in sandbar size and increases in campsite area. Whether this strategy leads to increases in campsite area that meet the management objectives set forth by the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program for increasing the size of campsite area in critical and noncritical reaches remains uncertain.

Removal of vegetation may be another viable strategy for increasing the size of campsite area. Although most vegetation expansion is occurring in noncritical reaches, these sites tend to be larger in size and more numerous along the river corridor. Physically removing vegetation at these sites would likely accomplish little in terms of increasing recreational carrying capacity, because many of these sites can still accommodate large river groups despite having increases in vegetation cover. Instead, targeting smaller sites in critical reaches and focusing on removal of groundcover shrubs such as arrowweed and camelthorn (and (or) removal of tamarisk that is impacted by tamarisk beetle herbivory) would likely be the most practical and successful vegetation removal strategy. [2]

|

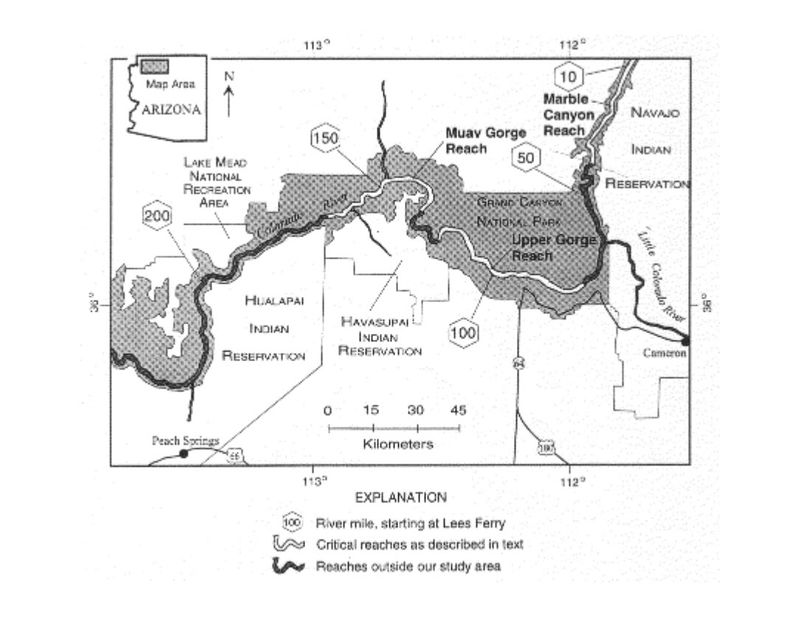

Critical Reaches

|

- Marble Canyon (river miles 9-41)

- Upper Gorge (river miles 71-114)

- Muav Gorge (river miles 131-165)

|

|

Information and Links

|

|

|

Recreation Projects

|

|

The Colorado River Runners Oral History Project is unparalleled within river running communities: though there are many regional organizations, no others have undertaken a project of this scope. GCRG unofficially began collecting oral history interviews in 1990 at “Woman of the River” Georgie White Clark’s 80th birthday party. Since that time, GCRG’s oral history project has produced nearly 100 interviews. Those interviews continue to serve as the centerpiece for each issue of our publication, the Boatman’s Quarterly Review.

Implemented in 1996 after the first historic “Flood Flow,” Adopt-a-Beach is a “watch dog” program that allows volunteer guides to keep close tabs on changes to the recreational resource that we depend upon – camping beaches in Grand Canyon. To be specific, this long term photo-matching, beach monitoring effort documents changes in sand deposition on camping beaches along the Colorado River resulting from Glen Canyon Dam flows. The results are disseminated to strategic river managers including Grand Canyon National Park, the Adaptive Management Program, and the Grand Canyon Monitoring & Research Center. Adopt-a-Beach is a fabulous example of a stewardship in action as we endeavor to “take care of our own back yard.” Please check out our extensive photo gallery as well as the Executive Summaries of past AAB reports. Full Reports are available upon request. And contact gcrg@infomagic.net if you’d like to volunteer! [3]

|

Presentations and Papers

|

|

2018

- Before and After Monsoon Beach/Camp Photos PPT

- Hadley et al., 2018, Quantifying geomorphic and vegetation change at sandbar campsites in response to flow regulation and controlled floods, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona: River Research and Applications

- Hadley et al., 2018, Geomorphology and vegetation change at Colorado River campsites, Marble and Grand Canyons, Arizona: U.S. Geological Survey Report data

- Neher et al., 2018, Exploring convergent validity between willingness to pay elicitation methods—An application to Grand Canyon whitewater boaters: Journal of Environmental Planning and Management

2017

2016

2015

2014

- Hadley. 2014. Geomorphology and vegetation change at Colorado River campsites, Marble and Grand Canyons, AZ, unpublished MS Thesis, School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability, Northern Arizona University, 158 p.

- Kaplinski et al. 2014. Colorado River campsite monitoring, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, 1998-2012, USGS Open-file Report: 2014-1161, 32 p.

2013

2012

2010

- Hazel et al. 2010. Sandbar response in Marble and Grand Canyons, Arizona, following the 2008 high-flow experiment on the Colorado River: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5015, 52 p.

- Kaplinskiet al. 2010. Colorado River campsite monitoring, 1998–2006, Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, in Melis et al. eds., Proceedings of the Colorado River Basin Science and Resource Management Symposium, November 18-20, 2008, Scottsdale, Arizona: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2010-5135, 275-284 p.

|

|

|

|

In Bishop et al. (1987; on page 410 of the 30 page report: “Grand Canyon Recreation and Glen Canyon Dam Operations: An Economic Evaluation) fluctuating flows are defined as any operation where the daily flow fluctuation was equal to or more than 10,000 cfs/day. Bishop treated daily flow fluctuations of less than 10,000 cfs/day as “constant flow releases.” Bishop identified that this “10,000 cfs threshold was determined to be the point at which fluctuations begin to be perceptible to recreationists.”

Additionally, Stewart et al.’s (2000) follow-up of the Bishop et al. (1987) study found that angler’s did not identify river level fluctuations, at least under the MLFF operating regime, as an issue. Based on information from Stewart et al (2000) and Bishop et al. (1987), any flow fluctuation below 10,000 cfs/day should be treated the same as a steady flow release.

|

Other Stuff

|

|

|