Updates

|

The Brown Trout Workshop

Scheduled for September 21-22 (8:30am - 5pm and 8:30am - noon) in Tempe after the AMWG meeting.

Action requested. Proposed draft motion AMWG meeting 2/15/17:

The AMWG believes that before moving forward with any new actions to manage brown

trout in the Lees Ferry reach of the Colorado River, it would be beneficial to work to

develop a plan based on the most up to date information and that has involvement

from interested members of the AMWG. Accordingly, the AMWG requests that the

Secretary of the Interior direct the National Park Service, and request the Arizona Game and

Fish Department, to organize and facilitate a workshop among scientists, managers, tribes,

and interested stakeholders to address:

- The root causes of the increases in brown trout,

- The risks associated with an expanding brown trout population to a quality rainbow trout fishery in Lees Ferry and the recovery/conservation of humpback chub and other native fish down river,

- The pros and cons of different management options to address those risks, and

- The research needs to support more informed decisions moving forward.

The workshop should also review the efficacy of the current High Flow Experiment protocol in light of new

scientific information and how it could be modified to allow for more frequent Spring HFEs

to conserve sediment and enhance biological resources in the Colorado River below Glen

Canyon dam. Results from the workshop, and any recommended actions based on them,

should be reported to the TWG for consideration in development of the Triennial Work

Plan and presented to the AMWG at the August 2017 meeting.

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

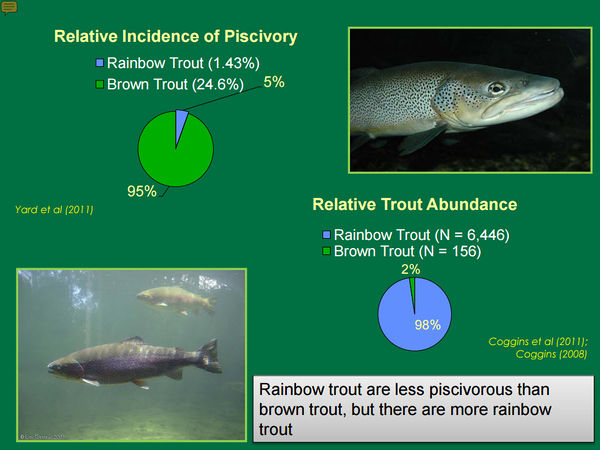

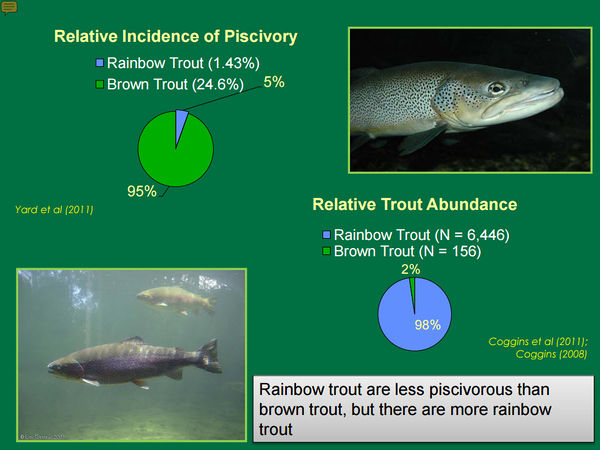

Brown trout are much more likely to eat other fish (piscivory) but since there are many more rainbow trout in the Colorado River between Glen and Marble Canyons, rainbow trout probably eat more fish numerically than brown trout. [1]

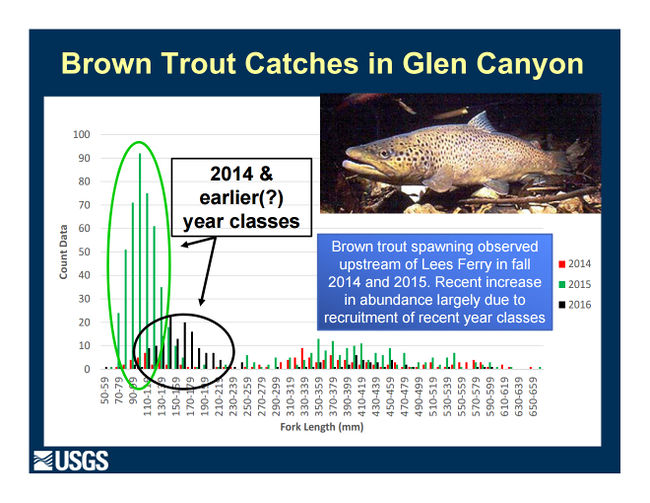

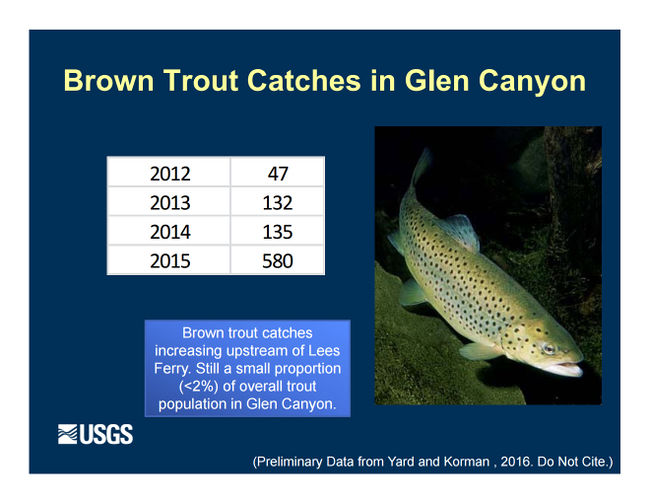

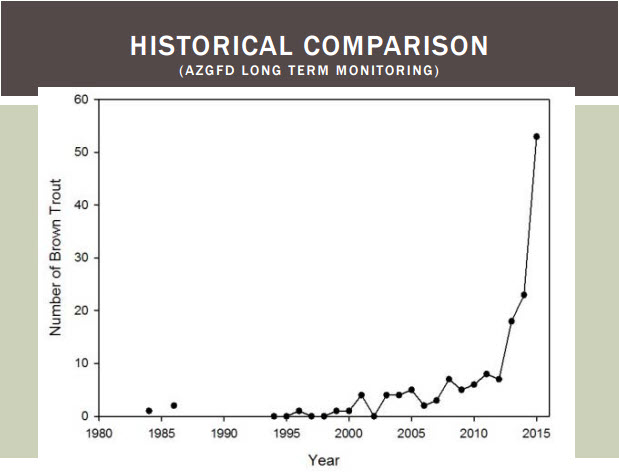

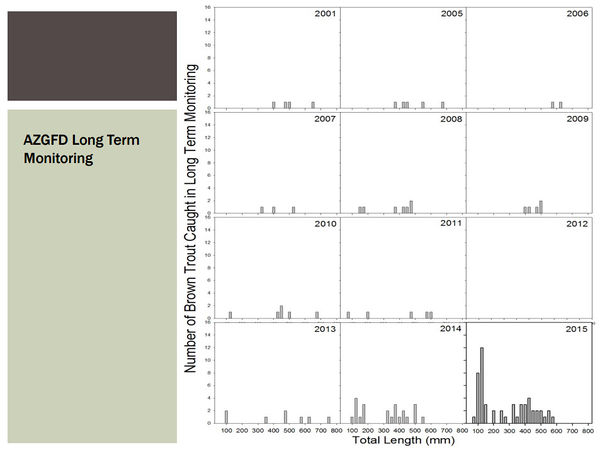

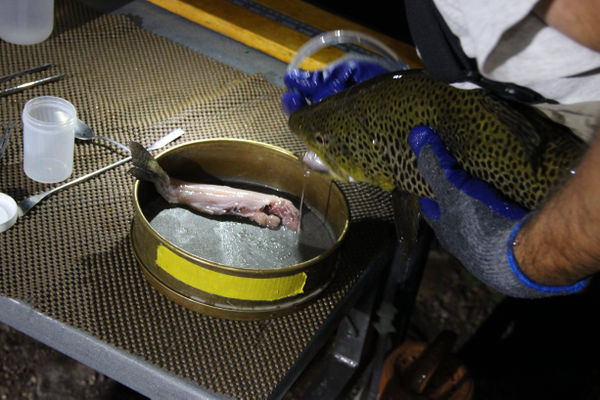

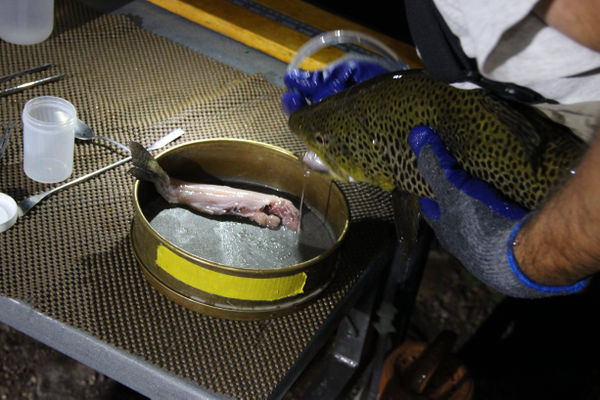

An increasing brown trout population in Glen Canyon could pose a problem for both the Lees Ferry rainbow trout fishery and native fish in Grand Canyon because brown trout eat both rainbow trout and native fish alike. Above is a photo of a brown trout collected during 2016 trout monitoring below Flaming Gorge dam that had just eaten a 10" stocked rainbow trout. |

|

Information and Links

|

|

|

Stakeholder Concerns

|

- the root causes of the increases in BT,

- the risks associated with an expanding BT population to a quality RBT fishery in Lees Ferry and the recovery/conservation of humpback chub and other native fish down river,

- the pros and cons of different management options to address those risks, and

- the research needs to support more informed decisions moving forward.

|

Questions

|

- Why are brown trout increasing in the Lees Ferry reach?

- Has the recent (winter 2014-15) decrease in the rainbow trout population allowed for increased brown trout spawning in the Lees Ferry reach because of decreased competition for spawning area and/or decreased egg predation by rainbow trout? If so, what caused the decrease in the rainbow trout population and what can be done in the future to avoid this from happening?

- Are increased numbers of brown trout in Lees Ferry a product of higher release temperatures?

- Do fall HFEs clean spawning substrate in the Lees Ferry reach leading to increased the spawning success of brown trout during their fall spawning season?

- Do fall HFEs increase the upstream migration of brown trout from other parts of the canyon resulting in more brown trout spawning in the Lees Ferry reach?

- Could delaying a fall HFEs to late December or January be effective in disrupting the brown trout spawn? When do brown trout spawn in Lees Ferry? Ans: Nov-Dec

- Is whirling disease selecting against rainbow trout production in the Ferry and thereby opening a niche for brown trout?

- Irregardless of the cause, what should we do about the increasing brown trout population currently found in the Lees Ferry reach?

|

Presentations and Papers

|

|

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2011

|

|

|

Tier 1 Trigger – Early Intervention Through Conservation Actions:

- 1a. If the combined point estimate for adult HBC (adults defined ≥200 mm) in the Colorado River mainstem LCR aggregation; RM 57-65.9) and Little Colorado River (LCR) falls below 9,000 as estimated by the currently accepted HBC population model (e.g., ASMR, multi-state).

-OR-

- 1b. If recruitment of sub-adult HBC (150-199mm) does not equal or exceed estimated adult mortality such that:

- Sub-adult abundance falls below a three-year running average of 1,250 fish in the spring LCR population estimates, or

- Sub-adult abundance falls below a three-year running average of 810 fish in the mainstem Juvenile Chub Monitoring reach (JCM annual fall population estimate; RM 63.45-65.2).

Tier 1 Trigger Response:

- Tier 1 conservation actions listed below will be immediately implemented either in the LCR or in the adjacent mainstem. Conservation actions will focus on increasing growth, survival and distribution of HBC in the LCR & LCR mainstem aggregation area.

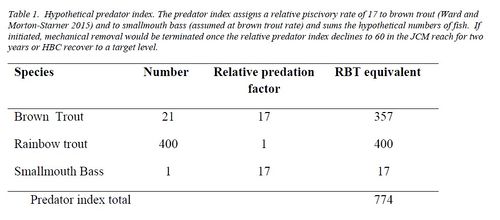

Tier 2 Trigger - Reduce threat using mechanical removal if conservation actions in Tier 1 are insufficient to arrest a population decline:

Mechanical removal of nonnative aquatic predator will ensue:

- If the point abundance estimate of adult HBC decline to <7,000, as estimated by the currently accepted HBC population model.

Mechanical removal will terminate if:

- Predator index (described below) is depleted to less than 60 RBT/km for at least two years in the JCM reach and immigration rate is low (the long term feasibility of using immigration rates as a metric still needs to be assessed),

-OR-

- Adult HBC population estimates exceed 7,500 and recruitment of sub-adult chub exceed adult mortality for at least two years.

If immigration rate of predators into JCM reach is high, mechanical removal may need to continue. These triggers are intended to be adaptive based on ongoing and future research (e.g., Lees Ferry recruitment and emigration dynamics, effects of trout suppression flows, effects of Paria River turbidity inputs on predator survival and immigration rates, interactions between humpback chub and rainbow trout, other predation studies).

|

Other Stuff

|

- "The divergent responses of brown trout and rainbow trout populations to the summer flood could be explained by competitive interactions. Brown trout are autumn spawners, whereas rainbow trout are spring spawners, and thus, YOY brown trout emerge earlier, are larger and may outcompete YOY rainbow trout (Gatz, Sale & Loar, 1987; Strange et al., 1992 ). Conversely , the autumn spawning of brown trout increases the risk of egg loss if autumn or winter floods occur. Several investigations showed that YOY brown trout or brook trout were generally more numerous than YOY rainbow trout except during years when floods scoured the eggs of the autumn spawners (Seegrist & Gard, 1972; Strange et al., 1992; Warren et al., 2009 ). " [10]

|

|