Scientific Review Suggests Reclassification of the Razorback Sucker from Endangered to Threatened - October 4, 2018

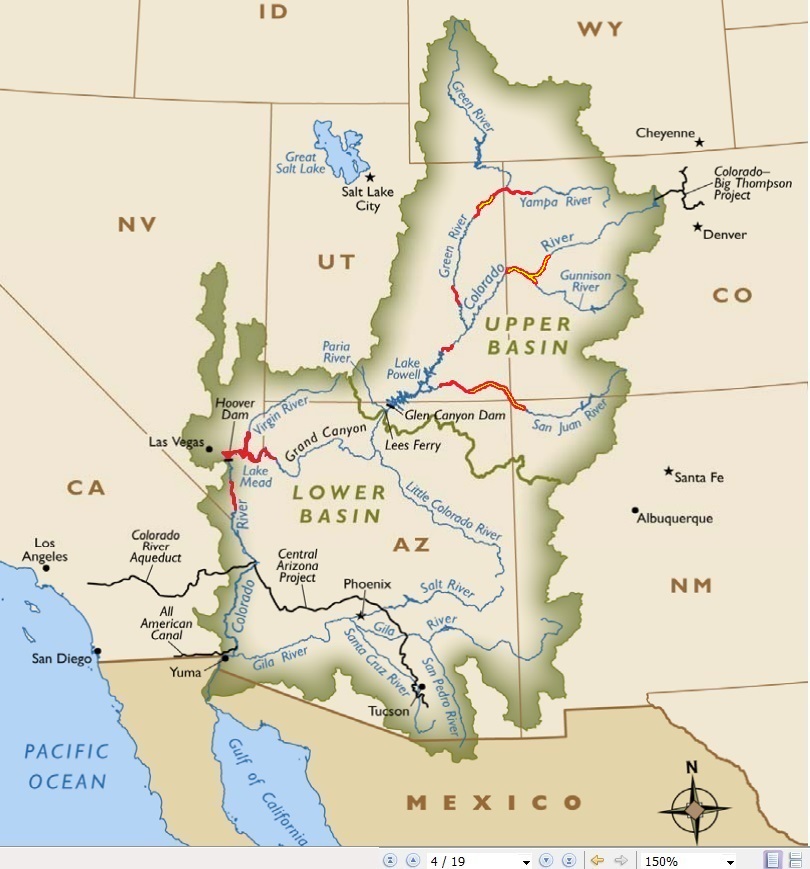

DENVER —The razorback sucker, a native fish found in the Colorado River basin is making a comeback thanks to the work of conservation partnerships between the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), states, federal agencies, Tribes, industry and environmental groups. The Service recently completed a species status assessment (SSA) and a 5-year status review, utilizing the best available science, that concluded the current risk of extinction is low, such that the species is no longer in danger of extinction throughout all of its range. The SSA explained that large populations of adults have been re-established in the Colorado, Green, and San Juan Rivers. Populations are also present in Lake Powell, Lake Mead, Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu. As a result, in the future the Service proposes to reclassify the fish from endangered to threatened.

The razorback sucker is the second of the four native Colorado River fish to be proposed for a change in status from endangered to threatened this year. The humpback chub has also been proposed for reclassification. The recovery success of these two fish would not have been possible without the strong partnerships and conservation efforts all along the river.

“Our partners along the Colorado River have restored flow, created habitat, removed nonnative predators, and reestablished populations across these species range,” said Tom Chart, Director of the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program. “These partnerships have improved conditions, proving long-term commitments are a key component to recovery.”

The razorback sucker was first documented in the Colorado River system in 1861 and historically occupied an area from Wyoming to Mexico, often travelling hundreds of miles in a single year. The species gets its name from the bony keel behind its head, which helps it stay put when flows increase. Razorback sucker are part of the lake sucker family, preferring low-velocity habitats, in either backwaters, floodplains or reservoirs and evolved in an ecosystem with one large-bodied predator: the Colorado pikeminnow. Young razorback sucker have few defense mechanisms, making them vulnerable to predation , especially from toothed nonnative predators. Changes in river flows and introduction of nonnative fish caused dramatic population declines. Thanks to intense management efforts, razorback sucker have made a remarkable comeback, especially in the Green and Colorado rivers. In the Green River in the mid-1990’s, the number of adults captured in a year could be counted on one hand; today, the population has rebounded to over 30,000 adults. The large populations are the result of successful hatchery programs. Stocked fish not only survive in the wild, but migrate, colonize new areas, return to historic spawning bars, and produce viable young.

Although this native fish is making a big step toward recovery, continued management efforts are needed to help the species cross the final threshold of being able to survive in sufficient numbers to reach adulthood. The Lake Mead population is the only population where juvenile fish routinely grow up into adults. All other populations are maintained through stocking efforts as the young are eaten by nonnative fish before they reach adulthood. Scientists are hard at work to determine the best ways to encourage survival of juveniles to naturally sustain the population. One wetland along the Green River managed for razorback sucker has produced over 2,000 young-of-year individuals in the past five years, the first substantial number of juveniles seen in over 30 years in the upper basin.

State, tribal, federal, and private stakeholders work together via the Upper Colorado River Endangered Fish Recovery Program, the San Juan River Recovery Implementation Program, and the Lower Colorado River Multi-Species Conservation Partnership to stock fish, create habitat, and continue monitoring programs to reduce threats to this species’ recovery.

In the 5-year review, the Service also recommends that the species recovery plan be revised to incorporate the best available scientific information on the species needs and actions that will eventually allow the Service to delist razorback sucker. Efforts to propose reclassification and to revise the recovery plan will be ongoing in the coming year. The proposed reclassification rule and the revised recovery plan will be made available for public comment in the future.

Status and distribution

- Listed as endangered and given full protection under the Endangered Species Act in 1991.

- Endangered under Colorado law since 1979.

- Protected under Utah law since 1973

- Historically, the razorback sucker was widespread and abundant in the Colorado River and its tributaries.

Today all populations of razorback sucker are supplemented with stocked fish except for the Lake Mead population. Lakes Mead and Mohave are the only population with wild fish.[5]

Working to recover the species

Actions being taken to recover the razorback sucker include:

- Managing water to provide adequate instream flows to create beneficial water flow

- Constructing fish passages and screens at major diversion dams to provide endangered fish with access to hundreds of miles of critical habitat

- Restoring floodplain habitat

- Monitoring fish population numbers

- Managing nonnative fishes

In addition, the Recovery Program works to reestablish naturally self-sustaining populations of razorback sucker through propagation and stocking. The Recovery Program maximizes the genetic diversity of wild broodstock used to produce fish in hatcheries to increase the likelihood that stocked fish can cope with local habitats.

In the Upper Colorado River Basin, razorback sucker are raised at two units of the Ouray National Fish Hatchery: the Grand Valley Unit in Grand Junction, Colorado, and the Ouray Unit in Vernal, Utah.

Razorback sucker raised at these facilities are stocked in the Colorado, Green, and Gunnison rivers. Efforts to reestablish populations through stocking demonstrate success as stocked fish survive to sexual maturity and reproduce. Fish stocked in the Colorado and Green rivers have been recaptured in reproductive condition and often in spawning groups. Captures of larvae in the Green and Gunnison rivers document reproduction and their survival through the first year is evidenced by subsequent captures of juveniles.

Stocked fish are moving between the Green, Colorado, and Gunnison rivers. This exchange of individuals between rivers suggests that razorback sucker may eventually form a network of populations or subpopulations.[6]

Recovery goals

Razorback sucker will be considered eligible for downlisting from “endangered” to “threatened” and for removal from Endangered Species Act protection (delisting) when all of the following conditions are met:

- Self-sustaining fish populations reach the required numbers in areas of the Green River subbasin and EITHER the Colorado River subbasin or San Juan Rivers, and the Lower Colorado River Basin, and a genetic refuge is maintained in Lake Mojave as identified in the chart below.

- The threat of significant “fragmentation” of the population has been removed. (Fragmentation refers to separation between fish populations caused by geographical distance or physical barriers.)

- Essential habitats, including primary migration routes and required stream flows are legally protected.

- Other identifiable threats that could significantly affect the population are removed.

Downlisting Criteria

Over a 5-year monitoring period:

- Maintain reestablished populations in Green River subbasin and EITHER in upper Colorado River subbasin or in San Juan River, each > 5,800 adults

- Maintain established genetic refuge* of adults in Lake Mohave

- Maintain two reestablished populations in lower basin, each > 5,800 adults

Delisting Criteria

For 3 years beyond downlisting:

- Maintain populations in Green River subbasin and EITHER in upper Colorado River subbasin or in San Juan River, each > 5,800 adults

- Maintain genetic* refuge of adults in Lake Mohave

- Maintain two populations in lower basin, each > 5,800 adults [7]

|