CRSP Act of 1956

|

|

CRSPA Section 1 (43 U.S.C. § 620) defines the purposes of the CRSP, which are (numbers added): In order to initiate the comprehensive development of the water resources of the Upper Colorado River Basin, for the purposes, among others, of

- regulating the flow of the Colorado River,

- toring water for beneficial consumptive use, making it possible for the States of the Upper Basin to utilize, consistently with the provisions of the Colorado River Compact, the apportionments made to and among them in the Colorado River Compact and the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, respectively, providing for the

- reclamation of arid and semiarid land,

- for the control of floods, and for the

- generation of hydroelectric power, as an incident of the foregoing purposes.

Note the use of the word INCIDENT. It is not INCIDENTAL. It is not secondary, lesser, subservient, nonexistent, or any other descriptor. It is RELATED TO the foregoing purposes. Section 1 of the Act also contains another reference to hydropower by its authorization “to construct, operate and maintain….dams, reservoirs, powerplants, transmission facilities and appurtenant works.”

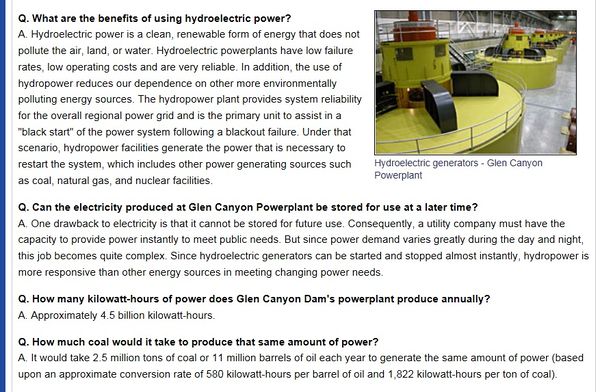

The protection and clarity about hydropower isn’t limited to these two references. Later in the Act, section 7 (43 U.S.C. § 620f) requires that the Glen Canyon Dam hydropower plants “be operated in conjunction with other Federal powerplants, present and potential, so as to produce the greatest practicable amount of power and energy that can be sold at firm power and energy rates”. Note the Act does not direct Federal power agencies to maximize revenues.

|

The Grand Canyon Protection Act (GCPA), The 1956 CRSP Act, and Hydropower

|

|

The 1992 GCPA purpose is defined in section 1802. Section 1802 is comprised of parts (a) and (b), which must be interpreted in tandem.

Section 1802(a): “The Secretary shall operate Glen Canyon Dam in accordance with the additional criteria and operating plans specified in section 1804 and exercise other authorities under existing law in such a manner as to protect, mitigate adverse impacts to, and improve the values for which Grand Canyon National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area were established, including, but not limited to natural and cultural resources and visitor use.”

However, in the same section Congress goes on to condition how 1802(a) must be implemented:

(b) “Compliance With Existing Law. -- The Secretary shall implement this section in a manner fully consistent with and subject to the Colorado River Compact, the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, the Water Treaty of 1944 with Mexico, the decree of the Supreme Court in Arizona v. California, and the provisions of the Colorado River Storage Project Act of 1956 and the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968 that govern allocation, appropriation, development, and exportation of the waters of the Colorado River basin. “

The key words are fully consistent AND SUBJECT TO. Some may argue that only water is addressed in 1802(b). CRSPA Sections 1 and 7 explicitly create the inextricable link by law between water and hydropower.

The “consistent with and subject to” was also clarified in the early days of the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (GCDAMP).

|

GCDAMP, CRSPA, GCPA, and Hydropower

|

|

In 2000, the Solicitor of the Interior, in response to questions and requests from the GCDAMP, created a “Guidance Document”.

In “Authority” (referencing the AMP): “Since the GCPA is clear that it was not intended to modify the compacts or ’the provisions of the Colorado River Storage Project Act of 1956 and the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968 that govern allocation, appropriation, development, and exportation of the waters of the Colorado River Basin’ (GCPA, section 1802(b)), any operational changes under the auspices of the GCPA are clearly subordinate to and must fit within the constraints of those provisions.”

In other words, the GCPA did not modify the authorized purposes of the CRSPA, and the GCDAMP derives its authority from the GCPA. The United States cited to this history in its GCT v. US Memo in Opposition Dkt. 135 at p. 38, fn22.

As a sidenote, section 102 of the 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act (43 U.S.C. § 1501(a) also uses “incident” in the same way as CRSPA. This Act “added in” recreation and improving conditions for fish and wildlife.

|

Glen Canyon Dam, Hydropower, and LTEMP

|

|

In 2009, the United States District Court, through the GCT v. U.S. case, described Reclamation’s obligation in its operation of Glen Canyon Dam, calling out the importance of the

hydropower purpose. Judge David Campbell’s statement is direct, unequivocable, and continues to be cited in current legal briefs in the most recent litigation (Save the Colorado et al v. U.S.).

“Reclamation is charged with balancing a complex set of interests in operating the dam. Those interests include not only the endangered species below the Dam, but also tribes in the region, the seven Colorado River basin states, large municipalities that depend on water and power from Glen Canyon Dam, agricultural interests, Grand Canyon National Park, and national energy needs at a time when clean energy production is becoming increasingly important.”

In 2012, following an extensive facilitated process, the Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, supported the “DFC Report” (Desired Future Conditions), which was the AMWG’s consensus view of what goals the Adaptive Management Program should strive for. Page 1 of the “DFC Report” cites sections 1802(a) and 1802(b) of the GCPA, along with Judge Campbell’s statement (above). The anticipated next steps beyond the DFCs were going to be quantifying those that hadn’t been quantified (hydropower had established metrics), through the LTEMP. As we see today, the AMP is still struggling with metrics for some of the resource goals.

DFCs were the precursors to the objectives in LTEMP. Power was a standalone DFC, later morphing into the LTEMP objective to “Maintain or increase Glen Canyon Dam electric energy generation, load following capability, and ramp rate capability, and minimize emissions and costs to the greatest extent practicable, consistent with improvement and long-term sustainability of downstream resources.”

|

Drought Contingency Plan (DCP) Agreements

|

|

GCD operations, and therefore the GCDAMP, are affected by the 2019 DCP Agreements. Page 1, the Background and Objectives, is very explicit as to hydropower:

2. Maintain the ability to generate hydropower at Glen Canyon Dam so as to protect:

a. Continued operation and maintenance of the CRSPA Initial Units and participating projects authorized under the 1956 Colorado River Storage Project Act, as amended (“CRSPA”);

b. Continued implementation of environmental and other programs historically funded by CRSPA revenues that are beneficial to the Colorado River system;

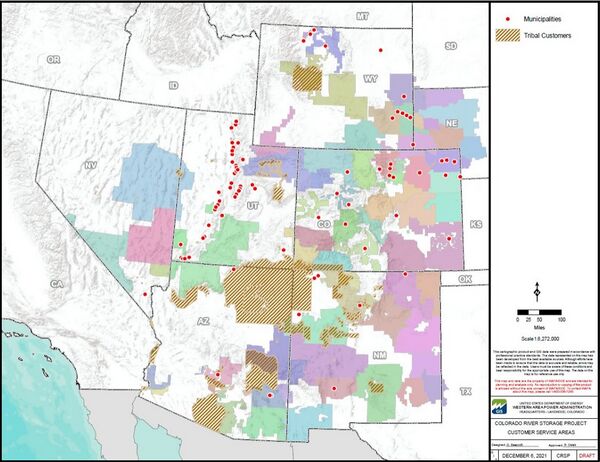

c. Continued electrical service to power customers including municipalities, cooperatives, irrigation districts, federal and state agencies and Native American Tribes, and the continued functioning of the western Interconnected Bulk Electric System that extends from Mexico to Canada and from California to Kansas and Nebraska; and

d. Safety contingencies for nuclear power plant facilities within the Colorado River Basin.

|

Western Area Power Administration (WAPA)

|

|

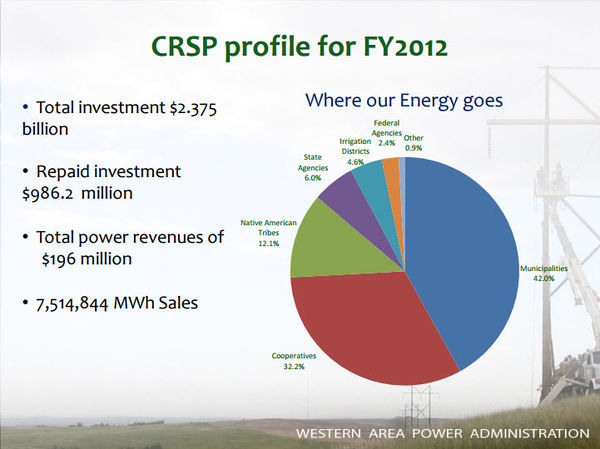

WAPA's Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP) is one of five of its regions. Our main offices include a Headquarters office in Lakewood, Colorado; regional offices in Salt Lake City, Utah; Billings, Montana; Loveland, Colorado; Phoenix, Arizona; and Folsom, California. CRSP's Energy Management and Marketing Office (EMMO) is located in Montrose, Colorado.

The CRSP Region carries out WAPA’s mission in Arizona, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Wyoming and Texas. We sell about 5,300 gigawatthours to cities and towns, rural electric cooperatives, Native American tribes, irrigation districts and federal and state agencies. This is enough energy to provide electric power for a year to 1.2 million homes.

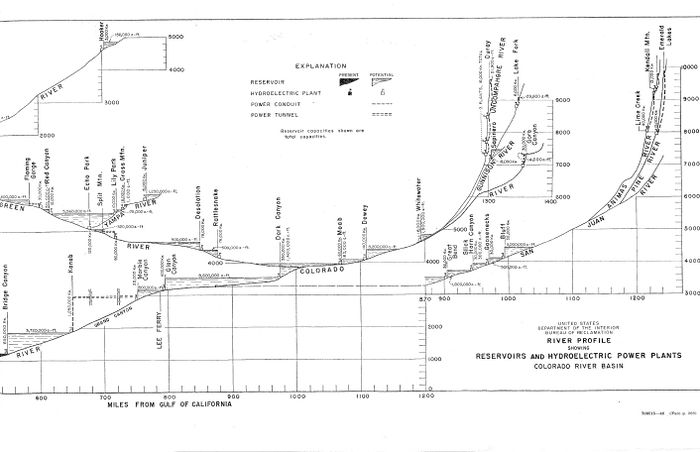

CRSP markets power from the Colorado River Storage Project, its participating projects (Dolores and Seedskadee) and the Collbran and Rio Grande projects. These resources comprise 11 powerplants located in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming and are marketed together as the Salt Lake City Area/Integrated Projects. We also market power from the Provo River Project and Olmsted Project in Utah; and the Falcon-Amistad Project in Texas. Transmission service is provided by transmission facilities in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming either owned or leased by WAPA.

We work together with our customers to provide new products and services tailored to their individual needs and are strongly committed to protecting the delicate balance of the Colorado River. Agencies that manage the river’s resources must weigh many interests, including flood control, drought mitigations, irrigation, recreation, hydropower, endangered species and historic properties. CRSP engages with all interested stakeholders in balancing these interests with the needs of water and electrical energy customers.

Since the 1980s, for example, we have been actively involved in ongoing environmental studies with diverse stakeholders regarding operations at Glen Canyon Dam. These and similar studies at Flaming Gorge Dam and the Aspinall Units represent WAPA’s commitment to engage with other interested parties in best managing the resources of the Colorado River and its tributaries. [2]

|

Colorado River Energy Distributors Association (CREDA)

|

|

CREDA is a regional association whose members include more than 155 municipal and rural electric cooperative utilities in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. CREDA members serve nearly three million electric consumers in these six states. CREDA’s member utilities purchase more than 85 percent of the power produced by the Glen Canyon and Flaming Gorge Dams and other features of the Colorado River Storage Project (CRSP). CREDA member utilities are consumer-owned, not-for-profit utilities whose primary responsibility is to provide reliable, low-cost service to the consumers they serve. [3]

|

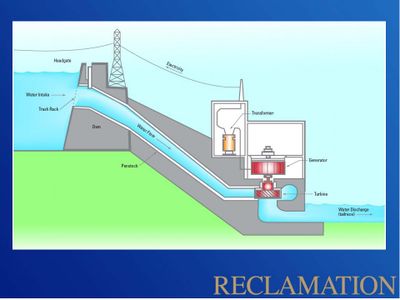

How do operations at Glen Canyon Dam fit into operations with other CRSP hydropower units?

|

|

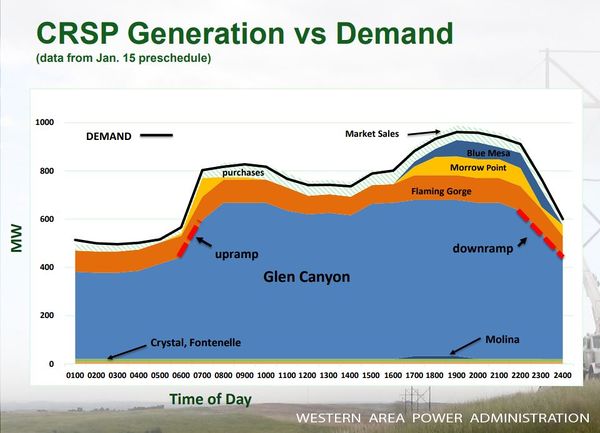

Glen Canyon Dam operates in conjunction with the other CRSP facilities to meet the contractual demands of CRSP customers. Glen Canyon is the largest asset in the CRSP portfolio and provides much of the baseload, with some load following, for CRSP customers. Blue Mesa and Morrow Point provides an example of "hydropeaking" with generation only occurring during peak hours.

|

What is Regulation and how does Glen Canyon Dam provide it?

|

|

As a control area operator, Western “regulates” the transmission system within a prescribed geographic area. Western is required to react to moment-by-moment changes in electrical demand within this area. Regulation means that “automatic generation control” will be used to adjust the power output of electric generators within a prescribed area in response to changes in the system frequency, time error, and tie-line loading, to maintain the scheduled level of generation in accordance with prescribed NERC criteria. The “record” used to calculate the degree to which Western is responding to these change on the transmission system is called the “ACE” - Area Control Error.

Hydro facilities such as Glen Canyon have an inherent design that allows them to respond rapidly to changes in power system demands. Other control area operators, across the nation, that do not have hydropower plants must either build small units (natural gas or oil-fired being the most likely) or add this capability to the design of larger units.

The transmission system that Western distributes power through is dynamic. Load requirements are constantly changing as a result of either the demands of the customers connected to it or changes that occur in other interconnected power systems. Western maintains the ACE signal to record its response to the fluctuations in system “loading”; (an effort to maintain a balance between power being consumed and power being generated - described above). If more demand is placed on the transmission system than is being generated, the resulting ACE is negative. Generators automatically respond to this condition by increasing generation. If demand is less than generation, ACE is positive. Generators automatically respond to this condition by reducing generation. The targeted ACE is zero.

The ACE signal that is sent to Glen Canyon where it is effectively added to, or subtracted from, the existing scheduled hourly generation base point. Therefore, at any moment during the day or night, Glen Canyon might be producing more or less power than the current hourly megawatt schedule.

The ACE signal is transmitted to Glen Canyon Dam every four seconds. The NERC requirement for regulation is that the ACE must “cross” the zero target every 10 minutes. The frequent “swings” in generation are described in the MOU signed by Reclamation and Western (4):

“These changes which occur many times during the hour are both positive and negative in relation to the schedule. The resulting output from Glen Canyon generators is an envelope of generation swings that are frequent, small in magnitude, the average of which approximates the original schedule.”[4]

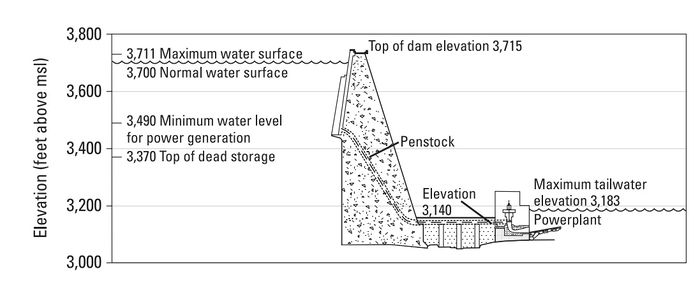

In addition to daily scheduled fluctuations for power generation, the instantaneous releases from Glen Canyon Dam may also fluctuate to provide 40 megawatts (mw) of system regulation. These instantaneous release adjustments stabilize the electrical generation and transmission system and translate to a range of about 1,200 cfs above or below the hourly scheduled release rate. Under system normal conditions, fluctuations for regulation are typically short lived and generally balance out over the hour with minimal or no noticeable impacts on downstream river flow conditions.

Releases from Glen Canyon Dam can also fluctuate beyond scheduled releases when called upon to respond to unscheduled power outages or power system emergencies. Depending on the severity of the system emergency, the response from Glen Canyon Dam can be significant, within the full range of the operating capacity of the power plant for as long as is necessary to maintain balance in the transmission system. Glen Canyon Dam typically maintains 30 mw (approximately 880 cfs) of generation capacity in reserve in order to respond to a system emergency even when generation rates are already high. System emergencies occur fairly infrequently and typically require small responses from Glen Canyon Dam. However, these responses can have a noticeable impact on the river downstream of Glen Canyon Dam. [5]

|

|

Links and Information

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Presentations and Papers

|

|

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2013

2010

2009

|

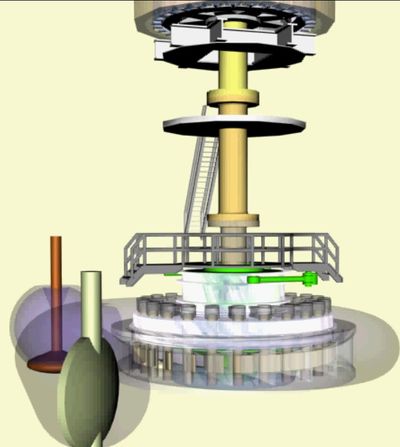

Adding Generation to the Bypass Tubes

|

|

|

What does it mean that "generation of hydroelectric power is an incident of the foregoing purposes" in the 1956 CRSP Act (43 U.S.C. § 620)?

|

|

In GRAND CANYON TRUST vs U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION, Grand Canyon Trust asserted that “[h]ydropower is an incidental benefit of every other stated purpose of the dam,” citing 43 U.S.C. § 620. Pl. Reply at p. 39. This is not a

correct statement of the law. The relevant portion of 43 U.S.C. § 620 provides “for the generation of hydroelectric power, as an incident of the foregoing purposes.” Congress did not provide that hydropower is “incidental to” or “an incidental benefit of” the Colorado River Storage Project. Hydropower is an “incident of” the other Congressionally defined purposes. Used in this manner and in this context, the word “incident” means “related to,” or “resulting from,” and does not mean that hydropower resources are an “incidental” or minor authorized purpose of the Colorado River Storage Project. [1]

|

Ramp rates and beach stability

|

|

Alvarez and Schmeeckle (2013) that found that bank stability is reached at a slope of approximately 14°. The erosion of intermediate slopes (18° - 22°) is controlled by seepage erosion, whereas the erosion of steep slopes (26°) is governed by mass failures. Erosion rates per diurnal cycle do not depend on ramp rates, but they increase with sandbar steepness. Therefore, steep sandbar faces would rapidly erode by mass failure and seepage erosion to shallower stable slopes in the absence of other erosion processes, regardless of dam discharge ramp rates. Their experiments only address seepage erosion and mass failure; increasing the daily magnitude and/or duration of peak discharge may increase the erosion of bars by turbulent sediment transport.

|

Other Stuff

|

|

|

|