Difference between revisions of "Tribal Resources"

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

Cellsworth (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 285: | Line 285: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|style="color:#000;"| | |style="color:#000;"| | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''2024''' | ||

| + | *[https://www.usbr.gov/uc/progact/amp/amwg/2024-02-29-amwg-meeting/20240229-HopiLong-termMonitoringTrip2023-508-UCRO.pdf Hopi Long-term Monitoring Trip 2023 ] | ||

'''2023''' | '''2023''' | ||

Revision as of 11:03, 23 August 2024

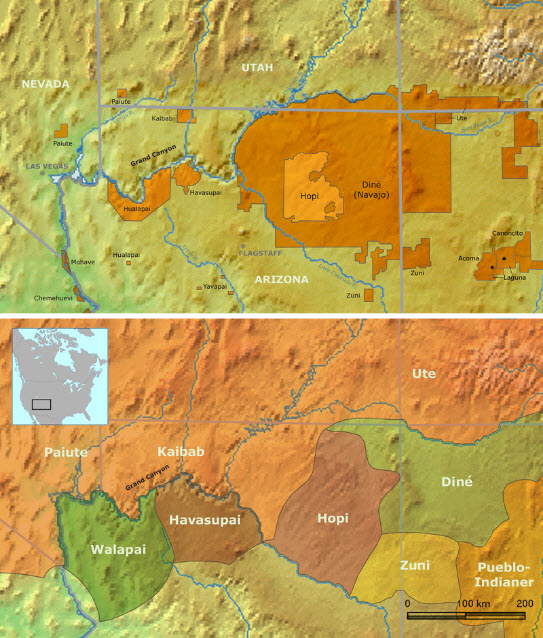

Homelands and reservations of Native Americans associated with the Grand Canyon https://oldwestdailyreader.com/native-american-tribes/ |

Tribal PerspectivesThe lower reaches of Glen Canyon and the river corridor through Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona, have been used by humans for at least 13,000 years. Today, at least nine contemporary Native American Tribes claim traditional cultural ties to this area. Grand Canyon National Park contains more than 4,000 documented prehistoric and historic sites, and about 420 of these sites are located in proximity to the Colorado River. The lower reaches of Glen Canyon contain an additional 55 sites. In addition to archaeological sites, cultural resources along the Colorado River corridor include historic structures and other types of historic properties, as well as biological and physical resources that are of traditional cultural importance to Native American peoples such as springs, unique landforms, mineral deposits, native plant concentrations, and various animal species. LTEMP Resource Goal for Tribal PerspectivesMaintain the diverse values and resources of traditionally associated Tribes along the Colorado River corridor through Glen, Marble, and Grand Canyons. Desired Future Condition for Cultural ResourcesTraditional Cultural Properties (TCPs):

|

| Tribal Ecological Knowledge |

Cultural Resources Library |

Tribal Perspectives |

|---|

Tribal perspectives on Aquatic Food BaseThe Zuni believe that macroinvertebrates are underwater species that are not yet ready for this world, and any disturbance to them could have negative consequences. The river’s life begins at the headwaters. The river is the umbilical cord to the earth, and through the Zuni religion, prayers, and songs there is also an invisible cord to the Zuni. This statement about underwater species relates to the Zuni history, as Zunis believe that their most ancient ancestors emerged onto this world only when they were ready for emergence. To force an aquatic species to change is to impede the species’ natural development and future progress, a violation of Zuni beliefs about the world’s natural order. (LTEMP Chapter 3, Page 65) Tribal perspectives on nonnative fish removalRepresentatives of the Pueblo of Zuni and the Hopi Tribe provided written comments to convey the perspectives of these two tribes regarding fish removal. The following text is the full, unedited set of comments, prepared by Kurt Dongoske (Pueblo of Zuni) and Michael Yeatts (Hopi Tribe). Participating Native American Tribes (Hopi Tribe and Pueblo of Zuni) have expressed, through government-to-government consultation, meetings with the Assistant Secretary for Water and Science, and through federal compliance processes associated with the National Environmental Policy Act and the National Historic Preservation Act, concerns to the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) regarding management actions described above involving fish suppression flows, mechanical removal of nonnative fish, and other lethal management actions. In the 2002–2004 GCMRC Biennial Work Plan, a proposal was made to conduct experimental mechanical removal of trout centered on the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers. At the time, the Hopi Tribe expressed concern about the killing of large numbers of fish and the specter of death that would be created by such activity in a culturally significant sacred area. The Hopi Tribe also understood the scientific desire to understand the effect that the non-native trout were having on the native, endangered humpback chub and if there were management options available to control the trout numbers, particularly if they were threatening the existence of the humpback chub. To make the study more culturally acceptable, the Hopi Tribe requested that the fish removed be used for a beneficial purpose, so that the life they were sacrificing wouldn’t be trivialized. The non-native fish were viewed as a fully alive component of the ecosystem, which were there through no fault of their own, and shouldn’t be needlessly punished. Perspectives of the Hopi Tribe have not significantly changed since the implementation of the original mechanical removal experiment. Killing large numbers of fish (or any other group of animals), unless there is an extraordinary circumstance, is fundamentally wrong! It is not the specific species of fish or the method of killing them that is at the heart of the Hopi concern; it is the view that their life is somehow less valuable and they are therefore expendable. Since 2006, the Hopi Long-term Monitoring Program asked about the appropriateness of removing non-native fish. To date, 46 percent of the Hopi respondents supported removal; 37 percent opposed it; and 17 percent were not sure. Those who support removal, however, clearly state that it should only be used if there is strong evidence that the non-native species is a real threat to the survival of a native species and that other causes are not more significant. Killing just because we think it might help, and we can do it, is not suitable justification. Secondly, they view killing the non-natives as the last resort. If they can be removed alive, that is preferred. Otherwise, they should be used as food for people or possibly for some other culturally appropriate purpose. Finally, the Hopi express puzzlement at the seemingly conflicting management goals of maintaining native fish and having a recreational trout fishery in the same river; and then fingering the trout as the threat to the native fish. While there are certainly many avenues being pursued that make managers feel that these divergent goals are possible, the simplest reading of the situation is that trying to achieve both of these goals is not appropriate. Over the past ten years, the Pueblo of Zuni has been the most vocal of the Tribes in expressing objection to these actions because they involve the taking of life without sufficient justification. The remainder of this section focuses on the Pueblo of Zuni’s objections to lethal management actions by situating those objections within the appropriate Zuni traditional cultural context. In doing so, a more informed and nuanced understanding of the Zuni position should be obtained. For the past twenty-five years, the Pueblo of Zuni has repeatedly emphasized to the Department of the Interior the important cultural, religious, and historical ties the Zuni people have to the Grand Canyon, Colorado River, and Little Colorado River. The Grand Canyon is the place of Zuni emergence into this current world at a place called Chimik’yana’kya dey’a, near Ribbon Falls in Bright Angel Canyon. The natural environment that Zuni people saw at Emergence became central to traditional Zuni culture. In fact, all of the plants that grow along the stream from Ribbon Falls to the Colorado River, and all the birds and other animals, springs, minerals and natural resources located in the Grand Canyon and its’ tributaries, have a central place in Zuni traditional cultural practices and ceremonial activities. The confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers is understood to be a spiritual umbilical connection between the Pueblo of Zuni and the Grand Canyon that is facilitated through the union of the Zuni River with the Little Colorado and the Colorado Rivers. The confluence is also held by the Zuni people to be an extremely important and sacred place because of its abundance of aquatic and terrestrial life that simultaneously expresses and represents the fertility of nature. The Colorado River is a particularly important place to the Zuni people because it was the location of an important historical event. This historical event was conveyed to Frank Hamilton Cushing, an American Anthropologist, by the Zuni in the late nineteenth century and is summarized below to convey the deep, intense, and remarkable significance that the Colorado River and the aquatic life within it indelibly hold for the Zuni people. “Shortly after Emergence, men of the Bear, Crane, and Seed clans strode into the red waters of the Colorado River and waded across. The men of the clans all crossed successfully. The women travelling with them carried their children on their backs and they waded into the water. Their children, who were unfinished and immature (because this occurred shortly after Emergence), changed in their terror. Their skins turned cold and scaly and they grew tails. Their hands and feet became webbed and clawed for swimming. The children fell into the swift, red waters. Some of the children became lizards, others turned into frogs, turtles, newts, and fish. “The children of these clans were lost to the waters. The mothers were able to make it to the other side of the river, where they wailed and cried for their children. The Twins heard them, returned, and advised all the mothers to cherish their children through all dangers. After listening to the Twins, those people who had yet to pass through the river took heart and clutched their children to them and safely proceeded to the opposite shore. “The people who successfully made it out of the river rested, calmed the remaining children, and then arose and continued their journey to the plane east of the two mountains with the great water between.” (Cushing, 1896, 1920, 1988; as summarized in Dongoske and Hays- Gilpin, 2016) As a consequence of this historical event, all aquatic life is recognized by present day Zunis to be descendants of those Zuni children who were lost to the waters, thus creating a strong and lasting familial bond to all aquatic life and a fundamentally important stewardship responsibility. It is precisely because of this familial bond and stewardship responsibility that the Pueblo of Zuni has for the past ten years communicated to the Department of the Interior objections to any management actions (for example, mechanical removal, trout suppression flows, piscicides) that entail the taking of aquatic life. The implementation of lethal fish management actions is contrary to Zuni worldview and environmental ethics. Annual ceremonial activities carried out by the Zuni are performed to ensure adequate rainfall and prosperity for all life. Zuni people pray not only for Zuni lands, but for all people and all lands. Zuni prayers are especially aimed at bringing precipitation to the Southwest. In order to successfully carry out Zuni prayers, offerings, and ceremonies necessary to ensure rainfall for crops and the prosperity of all life, Zuni must maintain a balance with all parts of the interconnected universe. The animals, including all aquatic life, birds, plants, rocks, sand, minerals, and water in the Grand Canyon convey special meaning and have significant material and spiritual relationships to the Zuni people. To needlessly take life causes an imbalance in the natural world and also disturbs the harmony and health of the spiritual realm and the Zuni peoples. Moreover, the Zuni recognize that there is a direct causal relationship between what happens in and to the Colorado River within Grand Canyon and the Pueblo of Zuni. According to Zuni religious and political leaders and illustrative of this point, when the initial mechanical removal efforts were occurring at the confluence of the Little Colorado and Colorado Rivers between 2003 and 2006, Zuni experienced an increased use of taser guns by Zuni police on Zuni community members. The increased use of tasers by Zuni police is viewed by the Zuni religious leaders as a direct adverse effect on the Zuni community that resulted from those mechanical removal efforts. To underscore this Zuni recognition of a cause/effect relationship between the Grand Canyon and Zuni, the Zuni religious leaders expressed their concern that the ongoing mechanical removal of brown trout and other non-natives from Bright Angel Creek by the National Park Service is contributing to an increase in the number of Zuni community members that are dying on a daily basis in Zuni. They emphasized that recognition that has existed since the time of Emergence. The implementation of lethal management actions to control non-native aquatic species, especially rainbow and brown trout, within the Colorado River through Glen and Grand Canyons creates a disproportionately negative impact, materially, spiritually, emotionally, and psychologically, on the Zuni people. These actions tend to emphasize strong reliance on reactionary management strategies rather than promoting proactive and productive approaches focused on identifying and controlling the antecedent environmental and structural conditions that promote or allow non-natives to enter and thrive within the system. The continued consideration of lethal management tools to address non-native aquatics demonstrates a disregard for the Zuni familial and stewardship relationship to aquatic life, a devaluation of the special relationship that the Zuni people have with the Grand Canyon and the Colorado River, and a blatant dismissal of previously expressed Zuni concerns to the U.S. Government. The comparison of management options directed toward the control of non-native aquatics by scientists and managers must respect Zuni perspectives and knowledge sovereignty by providing it equal standing with Western forms of knowledge production. To assume that the only viable method of controlling aquatic non-natives is through lethal means changes the expression and impression of the Colorado River as a waterway of life to a river of death. It is imperative that scientists and managers respective Zuni values through the integration of Zuni perspectives with scientific analyses to make them more compassionate, caring, holistic, and ultimately, productive for all life that depends on the Colorado River. Penned over 56 years ago and directed toward unrestrained pesticide use, Rachel Carson’s (1961:275) words expressed in Silent Spring, are prescient when considering the lethal management of non-native aquatics in the Colorado River. She wrote, “Life is a miracle beyond our comprehension, and we should reverence it even where we have to struggle against it…. The resort to weapons such as insecticides to control it is proof of insufficient knowledge and of an incapacity so to guide the processes of nature that brute force becomes unnecessary. Humbleness is in order; there is no excuse for scientific conceit.” [1] |